Скульптура в Израиле представляет собой совокупность скульптурных произведений, созданных в стране начиная с 1906 года — времени основания академии искусств «Бецалель». Процесс консолидации израильской скульптуры развивался под влиянием международного изобразительного искусства. В первые дни существования израильского искусства в Эрец-Исраэльрепатриировались многие известные скульпторы, искусство которых было синтезировано влиянием европейской школы и национальным самосознанием в Эрец-Исраэль, а затем в государстве Израиль.

Тенденция создания локального направления скульптурного искусства начала развиваться в 30-е годы XX века с возникновением произведений «ханаанейской» скульптуры, которые создавались под влиянием европейского искусства с мотивами, взятыми из восточного, в основном, месопотамского изобразительного искусства. Целью применения этих мотивов, сформированных в национальных условиях, было отражение взаимосвязи между сионизмом и родиной. Несмотря на амбициозность абстрактного искусства, зародившегося в Израиле в середине XX века под влиянием движения «Новые горизонты», целью которого было создание универсальной скульптуры, израильское скульптурное искусство обладало всеми характеристиками «ханаанейского» направления. В 70-е годы XX века, под влиянием международного концептуального искусства, израильское скульптурное искусство приобрело новые формы выражения. Эти методы существенно изменили определение скульптуры и позволили выразить политический и социальный протест, который до этого не находил отражения в израильском скульптурном искусстве.

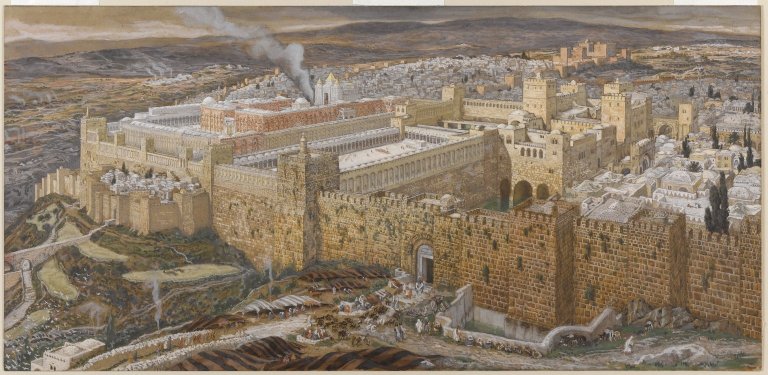

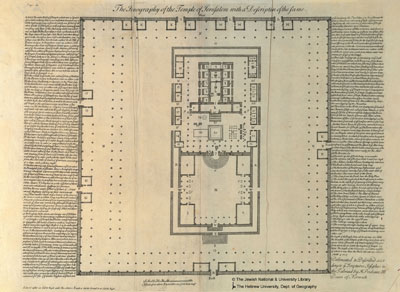

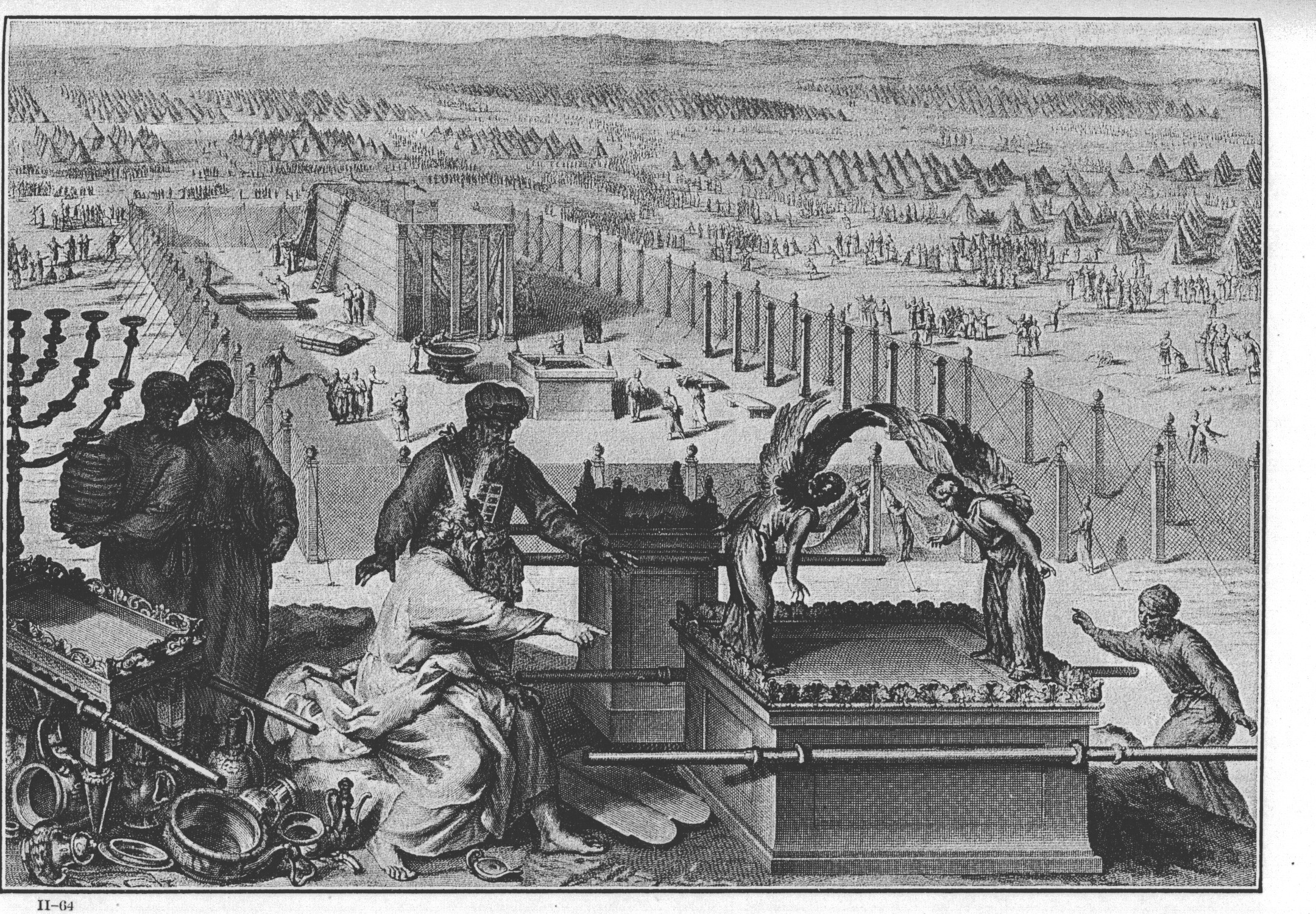

Опыт поиска внутренних национальных ресурсов для развития израильской скульптуры XIX века был проблематичным в двух отношениях. Во-первых, и художники, и еврейское общество в Израиле, не обладали достаточной национально-сионистской мотивацией, необходимой для сопровождения развития будущей израильской скульптуры. Во-вторых, в истории искусства не было традиций скульптурного творчества ни среди еврейских общин в Израиле, ни среди арабов и христиан, населявших Эрец-Исраэль в XIX веке. Исследования, проведённые Ицхаком Эйнхорном (ивр.), Хавивой Пелед (ивр.) и Ионой Фишером (ивр.), определили художественные традиции, характерные для того периода: в основном художественные оформления религиозного характера (еврейские и христианские), созданные для паломников, а также для экспорта и внутреннего потребления. Эти объекты включают декоративные календари, рельефные мыла, печати и т. д. с мотивами, заимствованными большей частью из традиций графического искусства[1].

В книге «Источники скульптуры Эрец-Исраэль»[2], израильский искусствовед Гидон Эфрат связывает период начала становления израильской скульптуры с основанием школы искусств «Бецалель» в 1906 году. Тем не менее, он отмечает трудности, возникавшие при характеристике этого вида изобразительного искусства в Израиле в тот период. Причиной послужило влияние различных направлений европейского изобразительного искусства на скульптурное творчество в Эрец-Исраэль при относительно небольшой численности скульпторов-израильтян, многие из которых работали в течение длительного времени в странах Европы.

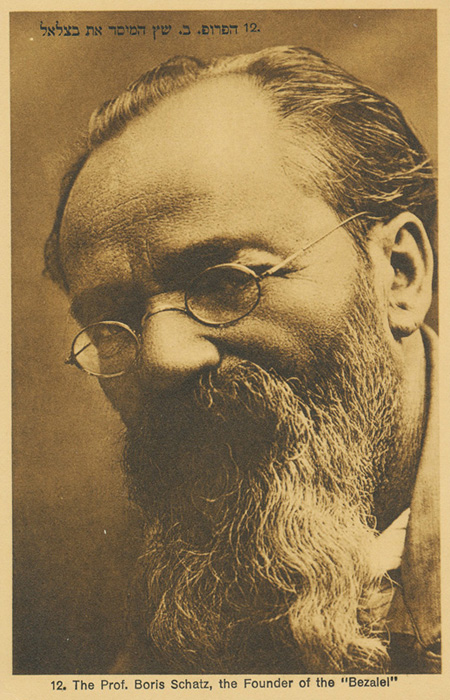

Вместе с тем, даже в художественной школе «Бецалель», которая была основана скульптором Борисом Шацем, направлению скульптурного изобразительного искусстване уделялось достаточно внимания, а специализацией школы была живопись и прикладное искусство графики и дизайна. В новой школе «Бецалель», созданной в 1935 году, скульптуре также не придавалось значения. Хотя в школе и было создано отделение скульптуры, но оно было закрыто через год, потому что воспринималось как вспомогательная студия, а не как независимое отделение. Вместо отделения скульптуры было открыто отделение керамики[3]. Действительно, в те годы были представлены персональные выставки крупных скульптур в музее «Бецалель» и Тель-Авивском музее изобразительных искусств, но это были отдельные случаи, которые не отражали связь скульптуры и трёхмерного искусства. Такое отношение к созданию и становлению скульптурного искусства в Израиле преобладало до 60-х годов XX века.

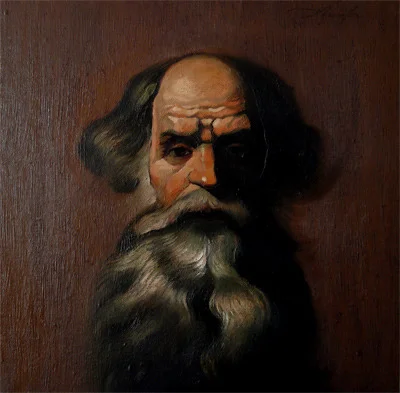

Началом становления скульптурного искусства в Израиле, как и израильского изобразительного искусства в целом, является основание школы «Бецалель» в Иерусалиме в 1906 году. Борис Шац, основатель «Бецалель», специализировавшийся в создании барельефных портретов и скульптур на еврейские темы в академическом стиле, изучал скульптуру в Париже у Марка Антокольского и был направлен им в Иерусалим.

Работы Шаца были пронизаны новым ощущением еврейско-сионистскойпринадлежности. Это нашло своё отражение в воплощении сюжетов и героев Танаха, которые были изображены в традициях европейского христианского художественного восприятия. Статуя Шаца «Маттатиягу Хасмоней» (ивр.) (1894), например, представляет национального лидера, еврейского священника Маттафию Хасмонея, держащего меч и наступившего ногой на тело греческого солдата. Это представление связано с идеологией победы «добра» над «злом», как это отражено, например, в скульптуре Персея (XV век)[4]. Серия памятных барельефов в честь лидеров Ишува также создана в традициях классического искусства в сочетании с декором в духе модерна. Влияние классического и ренессансного искусства проявилось во всех копиях скульптур Шаца, размещённых в доме инвалидов академии «Бецалель» в качестве идеальных моделей для учащихся школы. Среди этих работ была копия его статуи «Маттатиягу Хасмоней» (ивр.) (1894), представлющей национального лидера, еврейского священника, и копии — «Давид» (ивр.) и «Фото с дельфином» (1465) Андреа Верроккьо[5].

В направлениях школы «Бецалель» можно было выделить искусство живописи, иллюстрации и дизайна, в то время как работа в направлении скульптурного искусства была ограничена. Среди немногих семинаров, начатых в отделениях школы, были семинары резьбы по дереву и по изготовлению барельефов в память о лидерах сионизма и еврейского народа, а также семинары, посвящённые декоративно-прикладному искусству: техника листовой меди, инкрустация и тому подобное. В 1912 году была открыта кафедра резьбы по слоновой кости, также специализировавшаяся в прикладном искусстве[6]. В своей докладной записке Шац отметил деятельность учреждения в различных сферах, в том числе в создании каменных скульптур студентами для серии «Еврейский легион» и семинар резьбы по дереву[7].

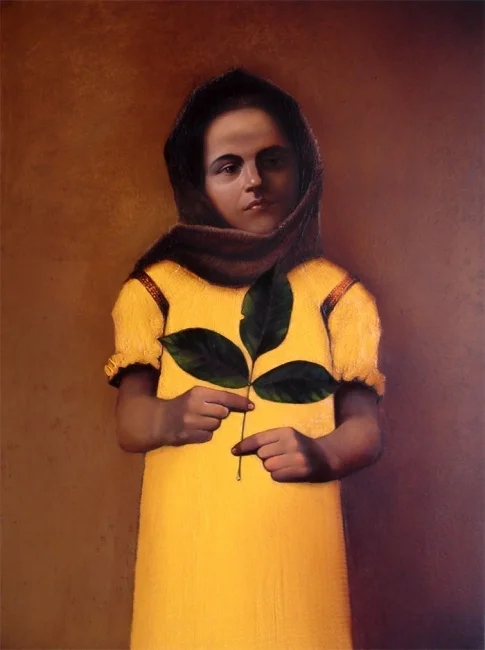

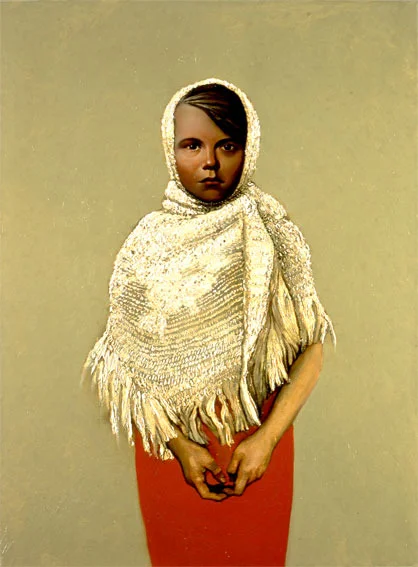

С первых дней создания школы «Бецалель» вместе с Шацем работали несколько других скульпторов. В 1912 году по приглашению Шаца в Израиль приехал Зеев Рабан, который преподавал в «Бецалель» скульптуру и анатомию. Рабан учился мастерству скульптуры в Мюнхенской академии художеств, а затем в парижском «Божаре» и в Бельгийской Королевской академии. Используя опыт своей графической практики, Рабан создал образные скульптурные барельефы в академическом, с восточными элементами, стиле. Так, композиция терракотовых фигур «Али и Самуил» (1914) представлена в образе йеменских евреев. Тем не менее, основная скульптурная деятельность Рабана заключалась в создании барельефных декоративных элементов[8].

Другие художники, также преподаватели «Бецалель», создавали реалистичные произведения в академическом стиле. Элиэзер Стрих, например, ваял бюсты лидеров Ишува. Другой художник, Ицхак Сыркин (ивр.), вырезал портретные барельефы из дерева и камня.

Основной вклад в скульптурное изобразительное искусство этого периода внёс Авраам Мельников, который работал в школе «Бецалель». Свою первую статую Мельников создал в 1919 году, после того как приехал в Эрец-Исраэль для службы в «Еврейском легионе». В конце 20-х годов Мельников создал несколько характерных стилизованных каменных скульптур из терракоты. Среди наиболее известных его работ серия символических произведений, представляющих еврейское национальное возрождение, такие как «Пробуждение Иегуды» (1925), памятники «Ахад-ха-Ам» (1928) и Максу Нордау (1928). Кроме того, работы Мельникова были представлены на выставке художников Израиля в Башне Давида (ивр.).

Памятник «Рычащий лев» (ивр.) (1928—1932) стал продолжением этой тенденции, оказавшись, однако, в тот период, вне рамок традиционного восприятия искусства еврейской общественностью. Работа по созданию памятника финансировалась Гистадрутом, Национальным комитетом и сэром Альфредом Мондом (ивр.). Монументальная статуя льва высечена из гранита под влиянием первобытного искусства и месопотамской скульптуры VII — VIII века до нашей эры[9]. В основном это отражено в анатомическом стиле дизайна персонажа.

В произведениях скульпторов, работавших в Израиле в конце 20-х и начале 30-х годов XX века, представлен широкий диапазон стилистических влияний. Среди скульпторов одни были приверженцами школы «Бецалель», а другие, особенно пришедшие в израильское искусство после обучения в Европейских школах живописи и ваяния, находились под влиянием постмодернизма или экспрессионизма (в основном, немецкого).

Среди художественных работ студентов школы «Бецалель» особенно выделялись скульптурные работы Аарона Прайвера (ивр.), который поступил в «Бецалель» в 1926 году. Его работы выполнены в сочетании реализма с архаичным стилем, или умеренным примитивизмом. Женские персонажи 30-х годов представлены в его работах посредством изогнутых линий и схематического изображения черт лица. Другой студент — Нахум Гутман, более известный своими картинами и иллюстрациями, в 1920 годуотправился в Вену, а затем в Берлин и Париж, где он обучался скульптурному мастерству. Его работы, представляющие собой миниатюрные скульптурные изображения предметов, носили экспрессионистский характер и выражали тенденцию символьного примитивизма.

Произведения Давида Озеранского (ивр.) продолжили традицию декоративных работ Зеева Рабана. Он помогал Рабану в создании скульптурных композиций для здания YMCA в Иерусалиме. Основной работой Озеранского в эти годы была скульптурная композиция «Десять племён» (1932), выполненная из десяти квадратных декоративных барельефов, символически изображающих десять культур, связанных с историей Израиля. Ещё одна работа Озеранского, созданная им в 1935 году — статуя льва перед зданием «Generali» в Иерусалиме[10].

Работы Давида Полуса (ивр.), который профессионально не не обучался ваянию, были выполнены в еврейской академической традиции, заложенной основателем школы «Бецалель» Борисом Шацем. Полус начал создавать скульптуры, совмещая творчество с работой каменщика в бригаде строителей. Его первой значительной работой, в которой было заметно стилистическое влияние школы «Бецалель», стала статуя «Давид Шеферд» (1936—1938), представленная на выставке в Рамат-Давиде. Другая монументальная скульптура «Памятник Александру Зайду» (ивр.) (1938), — отлитая из бетона конструкция, отображала характер «стража» — Александра Зайда, обозревающего Изреельскую долину. Центральная скульптура памятника была представлена реалистично, но в трактовке характера прослеживалась тенденция к восхвалению с акцентом на земное предназначение. Основой для памятника, созданного Полусом в 1940 году, послужили два тематических барельефа — «Лес» и «Пастух», выполненные в архаично-символическом стиле[11].

В 1910 году скульптор Хана Орлова уехала из Израиля во Францию, где начала учиться в Школе декоративного искусства (École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs). В её работах, в том числе созданных ещё в период обучения во Франции, прослеживается значительное влияние течений французского искусства начала XX века, в основном, кубизма. Объёмные, очерченные плавным контуром статуи, вырезанные из камня и дерева, посвящены в основном представителям французского общества того времени[12]. Однако, связь с родиной не прерывалась, и в 1935 году работы Ханы Орловой были выставлены на её персональной выставке в Тель-Авивском музее изобразительных искусств, а в 1949 году — в художественном музее Хайфы[13].

Другой скульптор, в работах которого заметно влияние кубизма — Зеев Бен-Цви. В 1928 году, после окончания школы «Бецалель», Бен-Цви продолжил обучение в Париже. По возвращении на родину, он в течение короткого периода преподавал скульптурное искусство в Новой школе «Бецалель». В 1932 году Бен-Цви представил свою первую выставку в государственном доме инвалидов «Бецалель», а год спустя его выставка открылась в Тель-Авивском музее изобразительных искусств. Статуя Бен-Цви «Пионер-сеятель» была представлена на выставке искусства Ближнего Востока (ивр.) в Тель-Авиве в 1934 году. Так же как и работы Ханы Орловой, эта работа, выполненная в стиле кубизма, достаточно реалистична и не является исключением из норм традиционного искусства[14]

Влияние тенденций французского реализма заметно в скульптурных работах таких европейских художников начала XX века, как Огюст Роден, Аристид Майоль и другие. Символьный характер замысла и формы был присущ и работам израильских мастеров ваяния и живописи: Моше Стреншуса (ивр.), Рафаэля Хамицера (ивр.), Моше Цифера (ивр.), Иосэфа Константа (ивр.)(Konstantinovski) и Дова Фейгина; большинство из них обучались скульптурному искусству во Франции.

Влияние немецкого искусства и особенно немецкого экспрессионизма заметно в работах группы художников, которые приехали в Израиль после обучения в различных городах Германии и в Вене. Такие художники, как Иаков Бранденбург, Труда Хаим, Лили Гомферц-Бятос, Георг Шницер создавали скульптурные образы, в основном портретные, используя палитру различных стилей, от импрессионизма до умеренного экспрессионизма.

Одной из этой плеяды была Батья Лишански (ивр.), которая училась живописи сначала в академии «Бецалель», а затем изучала искусство скульптуры в Парижской академии «Божар». После возвращения в Израиль под влиянием искусства Роденаона создала выразительные, подчёркнуто реалистичные скульптурные образы. Лишански известна как автор серии памятников, первый из которых — «Работа и защита» (1929), — был установлен на могиле Эфраима Чижика (ивр.), погибшего в бою в лесу Герцля. В характере этой скульптуры отражена сионистская утопия тех дней — героическая смерть за родную землю.

Заметное влияние на искусство этой группы художников оказало творчество Рудольфа Лемана, который начал преподавать скульптуру в собственной студии в конце 30-х годов прошлого века. Леман изучал искусство ваяния у немецкого скульптора Федермейера, специализировавшегося на создании изображений животных. В скульптурных образах Лемана отражено влияние экспрессионизма, что подчёркнуто выбором скульптурного материала и характером работ художника. Несмотря на общую оценку работ Лемана, важность изучения его методов создания произведений классической скульптуры из камня и дерева отмечали многие израильские художники.

В конце 30-х годов в Израиле была создана группа «ханаанейцы» — движение в литературе и искусстве, целью которого было уравнивание всех народов, живших на земле Израиля во 2-м тысячелетии до н. э., с еврейским народом, живущим в Израиле в XX веке, и создание новой культуры, нарушающей еврейскую традицию. Художником, которого отождествляли с этим движением, был скульптор Ицхак Данцигер, в 1938 году вернувшийся в Израиль из Англии, где он изучал изобразительное искусство. Предлагаемое Данцигером новое национальное «ханаанейское» искусство, антиевропейское, полное чувственности и экзотики Востока, отражало взгляды многих членов еврейской общины в Израиле. «Мечтой современников поколения, — писал Амос Кейнан после смерти Данцигера, — было объединиться в стране и на земле, чтобы создать образ, в частности, с атрибутами того, что находится здесь и у нас, и оставить благодаря этому особый след в истории. Только национализм представил собственный стиль экспрессионистской символической скульптуры, в духе современной британской скульптуры».[15].

Во дворе больницы, принадлежавшей отцу, в 1939 году Данцигер создал художественную студию, в которой работали молодые скульпторы: Биньямин Таммуз, Косо Элул (ивр.), Йехиэль Шеми (ивр.), Мордехай Гумпель (ивр.) и другие[16]. В этой студии Данцигер занимался преподавательской деятельностью, а также создал свои первые значительные работы «Нимрод» (1939) и «Шабазия» (1939). Кроме того, студия приобрела известность среди многих художников того времени, которые использовали её для творческого общения.

Сразу же после презентации статуя «Нимрод» стала основным «яблоком раздора» в культуре Израиля. Статуя Данцигера представила в образе Нимрода библейского охотника — худощавого юношу, обнажённого и необрезанного, с мечом, плотно прижатым к телу, и с соколом, сидящим на его плече. Образ, представленный Данцигером, напомнил примитивные скульптуры ассирийской, египетской и греческой цивилизаций в сочетании с европейским духом того времени. В статуе совместилась уникальная гомоэротичная языческаякрасота и идолопоклонство. Это сочетание стало центром критики со стороны религиозных кругов в еврейской общине. Но в противовес этому существовала и другая трактовка образа — видение в нём еврейского молодого человека новой формации. В 1942 году в израильской газете «Утро» было написано: «Нимрод это не просто статуя, он плоть от нашей плоти, дух нашей духовности. Он символ и памятник. Совокупность менталитета и отваги, монументальности, молодёжного бунта, указывающего на целое поколение… Нимрод будет вечно молодым…»[17].

Презентация статуи, состоявшаяся на «Первой групповой выставке художников Эрец-Исраэль» в мае 1944 года в театре Габима[18], подняла дебаты вокруг «ханаанейской» группы. После выставки Данцигер рассказывал, что к нему обратился Ионатан Ратош, один из основателей движения, и попросил встретиться с ним. Критика «Нимрода» и «ханаанейцев» исходила не только со стороны религиозной общественности, которая протестовала против идолопоклонства, но и со стороны представителей светской культуры, протестующих против отрицания еврейского в еврействе. Таким образом, «Нимрод» оказался в центре спора, который начался намного раньше, чем была создана сама статуя.

Хотя в ретроспективе Данцигер не видел статую Нимрода в качестве образца израильской культуры, многие художники восприняли положительно скульптурное искусство ханаанейской группы. В 70-х годах XX века в израильском искусстве появились скульптурные изображения идолов и символьные изображения, выполненные в традициях примитивизма. Кроме того, влияние этой скульптуры распространилось на изобразительное искусство группы «Новые горизонты», многие представители которой создавали «ханаанейскую» скульптуру в начальный период своего творчества.

Дополнительным аспектом новых тенденций был растущий интерес к израильскому пейзажу. Выполненные под влиянием лэнд-арта, такие работы отражали диалектическую связь между пейзажем Эрец-Исраэль и пейзажем Востока. Объектами многих произведений стали ритуальные и метафизические явления и характеры, что позволяет проследить непосредственное влияние на пейзажную скульптуру того периода искусства «Ханаанейской группы» и абстрактного искусства «Новых горизонтов».

Один из первых проектов такого рода в израильском концептуальном искусстве был предложен скульптором Йешуа Нойштейном (ивр.). В 1970 году Нойштейн в партнёрстве с Жоржет Белье и Жерардом Маркесом участвовал в разработке «Проекта Иерусалимской Реки». В проект были включены усиленные „рамколями“ звуки, производимые шумом течения воды в Восточном Иерусалиме, на территории от подножия Абу-Тор и Сент-Клэр до Кедронской долины. Мнимая река создавала не только причину для вне-музейного искусства, но также и иронический намёк на мессианское чувство искупления после Шестидневной войны, в духе книг Иезекииля и пророка Захарии (гл. XIV)[30].

Концептуальный аспект в развитии и трансформации израильского пейзажного искусства отражён в работах Ицхака Данцигера, в течение нескольких лет посвящённых местному пейзажу. По мнению Данцигера, было необходимо восстанавливать нарушенные отношения между человеком и средой его обитания. Этот подход привёл его к разработке проектов, направленных на возрождение достопримечательностей, экологии и культуры. В 1971 году работа Данцигера «Навесной пейзаж» была представлена на выставке в Музее Израиля. В этой работе, выполненной из подвешенной ткани, на которой были изображены пятна различных цветов, нанесена пластиковая эмульсия, волокна целлюлозы и химические удобрения, при помощи света и системы орошения Данцигер вырастил траву. С помощью слайдов, представленных вместе с тканью, он показал, какой ущерб природе наносит современная индустриализация. Лейтмотивом выставки стало искусство, посвящённое единению человека и природы[31].

«Исправление» пейзажа, как миссия искусства, нашло своё продолжение в проекте «Реабилитация карьера Нешер», на западных склонах горы Кармель. Проект разрабатывался Данцигером совместно с экологом Зеевом Нава и почвоведом Джозефом Морина. Целью проекта, который так и не был завершён, было применение различных технологических и экологических средств для создания на остатках карьера новой окружающей среды. «Природа не возвращается в своё прежнее состояние, — говорил Данцигер, — нужно найти способ для создания новой общей концепции чтобы использовать природу заново»[32]. По завершению первого этапа проекта в 1972 году результаты усилий по восстановлению были представлены на выставке в Музее Израиля.

В 1973 году Данцигер начал собрать материалы для книги, документирующей его работу. При подготовке книги были собраны документы из археологических мест отправления культа и тех регионов современного Израиля, которые послужили автору источником вдохновения. Книга «Место» с фотографиями работ, эскизами к проектам и экологическими идеями, представленными в значении абстрактного скульптурного искусства (такими, как «Сбор дождевой воды» и тому подобными), увидела свет в 1982 году, уже после смерти Данцигера. Один из ишувов, описанных в этой книге, Бустан Хият на реке Сих в Хайфе, был основан Азизом Хиятом в 1936 году. Наряду с семинарами, проводимыми Данцигером в Технионе, и реализацией дизайнерского опыта, он также уделял много внимания поддержке и развитию зелёной зоны Бустана.

В 1977 году в ходе церемонии в честь открытия мемориала бригаде «Эгоз» на Голанских высотах было посажено 350 саженцев дуба. При создании памятника Данцигер, исполнявший обязанности арбитра в конкурсе по планированию и дизайну, предложил уделить особое внимание ландшафту, что по его мнению придало бы мемориалу более функциональный характер: «Мы понимали, что вертикальная структура, выполненная в виде скульптуры, пусть даже очень впечатляющей, не может конкурировать с горной грядой. Поднимаясь, мы обнаружили, что горные породы, которые выглядели издалека как текстура, являются подлинными и обладают особым характером»[33]. Это подтвердило и исследование святых для бедуинов и палестинцев мест в Израиле, мест, где деревья рядом с могилами праведников являются особыми характерными символами. Подчиняясь силе эмоций, люди вывешивают на эти дубы яркие синие и зеленые цветные ткани и загадывают желания[34].

Молодые художники, последователи Данцигера, создали в 1972 году серию работ в местности, находящейся между кибуцем Мецер и арабской деревней Мейсер. Миха Ульман, с помощью молодых людей из обеих общин, вырыл по яме в каждой из них и произвёл символический обмен землями. Моше Гершуни организовал церемонию, в ходе которой разделил землю кибуца Мецер между своими друзьями. Авиталь Гева (ивр.) открыла на территории, разделяющей две общины, импровизированную библиотеку, собранную из книг, напечатанных на бумаге фабрики «Амнир»[35].

Вдохновлённый идеями Данцигера, Игаль Тумаркин (ивр.) в начале 1970-х годов завершил серию работ под названием «Ограды из оливковых деревьев и дубов», которая включала произведения эфемерной скульптуры, окружённые деревьями. Так же, как Данцигер, Тумаркин связывал эти работы с формированием жизнедеятельности поп-культуры, в частности, в арабских и бедуинских деревнях, и создавал их на своеобразном морфологическом художественном языке, следуя методу создания скульптуры бриколажа «Бедность».

Тематика некоторых работ относится не только к мирному сосуществованию, но и к израильской политике. Такие работы Тумаркина, как «Распятие Земли» (1981) и «Бедуинское распятие» (1982), тематически посвящены изгнанию палестинцев и бедуинов и установлению на их землях «столпов распятия»[36].

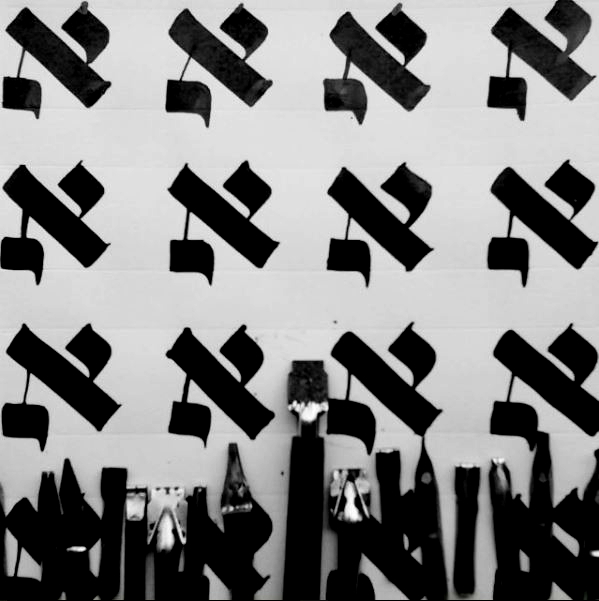

Ещё одной группой, действовавшей в том же духе создания метафизических произведений еврейской тематики, была группа «Левиафан» (ивр.), куда входили Авраам Офек, Михаэль Гробман и Шмуэль Аккерман. В 1975 году они опубликовали манифест, в котором охарактеризовали современное положение искусства, ссылаясь на три основных элемента: примитив, символ и знак. В работах этой группы сочетались концептуальное искусство, искусство лэнд-арта и еврейская символика. Авраам Офек в основном интересовался связью скульптуры с символизмом и религиозными образами. В серии его работ представлены зеркальные отражения букв иврита, слова с религиозной символикой, каббалистические и другие изображения ландшафтов или зданий. В работе «Световые сигналы» (1979), например, буквы спроецированы на людей, ткани и землю Иудейской пустыни. В другой работе — «America, Аfrica, Green Card» (1980) — слова изображены на стенах одного из дворов Тель-Хай[37].

Влияние изобразительного искусства, начавшего развиваться в США в 60-х годах XX века, проникло в израильское искусство в конце того же десятилетия с деятельностью группы «Десять плюс» (ивр.) во главе с Рафи Лави, и группы «Третий глаз» под управлением Жака Катмора (ивр.)[43]. Для критического анализа пространства многие скульпторы использовали различные возможности, которые предоставил им технический прогресс. Несмотря на то, что в работах того периода прослеживается отказ от необходимости реального физического представления, вместе с тем, очевидно однозначное отношение художников к пространству в политическом, социальном и гендерном аспектах.

Пинхас Коэн-Ган (ивр.), создал в эти годы серию работ политического характера. Композиция «Прикосновение к границе» (7 января 1974) представляет собой четыре железные решетки на границе Израиля, где были арестованы израильские граждане, и размещённую на них информацию о демографии страны. В работе «Действия в лагере беженцев в Иерихоне» отражены события, имевшие место 10 февраля 1974 года к северо-востоку от Иерихона, недалеко от Хирбет аль-Фаджр. Коэн-Ган изобразил свой собственный опыт иммиграции и опыт палестинских иммигрантов, построивших палатку, похожую на парус лодки. Коэн-Ган также инициировал «Призыв к Израилю через 25 лет, в 2000-м году». В этом призыве говорилось: «Беженцем является человек, который не может вернуться на родину»[44].

Художница Эфрат Натан (ивр.) создала серию произведений, отражающих разрыв отношений между зрителем и произведением искусства, в свете критики израильского милитаризма после Шестидневной войны. Среди наиболее известных её работ — скульптура «Голова», вырезанная из дерева маска на голове художницы. Натан надела её на следующий день после парада Цахаля в 1973 году и прошла по центральным улицам всего Тель-Авива. Форма маски в виде буквы «Т» напоминала крест или самолёт и ограничивала поле зрения[45].

В серии работ, созданных в 70-е годы скульптором Моше Гершуни, проявилось сочетание политической и художественной критики с поэзией. В его творчестве, которое стало известно в эти годы как концептуальная скульптура, проблема определения эстетического искусства рассматривалась как эквивалент политической проблемы в Израиле. Одним из произведений, отражающих эту тенденцию, была работа «Нежная рука» (1975—1978), в тематике которой Гершуни совместил газетный репортаж о злоупотреблениях в отношении палестинцев и печальное стихотворение о любви Залмана Шнеура, воспроизводимое голосом самого Гершуни, доносившимся из громкоговорителя, размещённого на крыше Тель-Авивского музея искусств. В этой работе минималистская и концептуальная эстетика была использована для критики сионизма и израильского общества[46].

Работы Гидона Гехтмана (ивр.) в эти годы были посвящены сложным отношениям между искусством и жизнью художника, а также диалектике между художественным представлением и реальной действительностью[47]. В работе, представленной в серии «Экспозиция» (1975), например, Гехтман изобразил церемонию бритья волос на теле при подготовке к операции на сердце, используя документальный стиль фотографии, медицинские записи и рентгеновские снимки, которые показывали клапан, имплантированный в тело. В другой работе, «Щётки» (1974—1975), волосы Гехтмана и членов его семьи были представлены в виде различных щёток-реликвий, размещённых в деревянных футлярах, сделанных в духе суровой минималистской эстетики.

Важной работой Гехтмана в тот период явилась композиция, представленная на выставке «Открытый семинар» (1975) в Музее Израиля. Выставка была посвящена подведению общественно-политического итога так называемого «еврейского труда» и включала работы Гехтмана как создателя нового отделения музея. На выставке Гехтман разместил некролог под названием «Еврейский труд» и фотографию арабских рабочих на строительных площадках. Хотя эта работа содержала изображение отдельных политических партий, она отчётливо показала многогранные отношения между художником и обществом.

Другой эффект постмодернистского подхода заключался в попытке нарушить смысл социальной истории. Искусство больше не рассматривалось как идеология, которая поддерживает или выступает против дискурса израильского гегемона в качестве основы для отражения плюралистического и открытого дискурса реальности. В публикации 1977 года «Политическая революция» высказывается мнение, что в «дискурсе идентичности» до сих пор не фигурируют слои общества.

В начале 80-х годов в израильском обществе начали появляться художественные произведения, раскрывающие тему Холокоста. В произведениях «второго поколения» появились образы и характеры, взятые из истории Второй мировой войныи объединённые в попытке идентификации их принадлежности к еврейству и к Израилю. Среди этих новаторских работ выделялись произведение Моше Гершуни «Красная чеканка: Театр» (1980) и работы Хаима Маора (ивр.). Более отчётливо эта тематика повторилась в 90-е годы. Большая группа произведений, созданных Игалем Тумаркиным (ивр.), состояла из монументальных работ, отражающих различные аспекты Холокоста: начиная от его ужасов и до его трактовки в цивилизованном мире. В произведениях Пенни Ясур, например, Холокост представлен в серии структур и моделей, в том числе, намёков и цитат, связанных с войной. Работа «Screens» (1996) — железнодорожная карта Германии в 1938 году в виде барельефа на каучуковых пластинах, впервые продемонстрированная на выставке «Документ», отражает связь между памятью государственной и личной[54]. Другие материалы, используемые Ясур в различных архитектурных пространствах, — металл и дерево, создают атмосферу отчуждённости и ужаса.

Важный аспект памяти Холокоста был связан с репатриацией и репатриантами в первые десятилетия государственности Израиля. Соответствующий художественный опыт сопровождался протестом против образа «израильского сабры» и особым вниманием к образам репатриантов. Скульптор Филипп Ранцер (ивр.) представил серию работ, изображающих иммигрантов и беженцев. В его работах, которые созданы как совокупность различных готовых материалов, отражено противоречие между постоянством и чувством нестабильности. Скульптура Ранцера «Коробка из Нес-Ционы» (1998) представляет собой восточного верблюда, несущего на спине жилище семьи самого Ранцера, расположенное (в прошлом) в Несс-Ционе. Фигуры членов семьи Ранцера представлены в виде скелетов[55].

В дополнение к теме Холокоста, в израильском искусстве 90-х годов появилась нарастающая тенденция отражения традиционных мотивов. Хотя в прошлом подобные мотивы появлялись в работах таких художников как Арье Aрох, Моше Кастель и Мордехай Ардон, в работах художников начала 90-х годов мир еврейской символики занял особое место. Среди художников, которые использовали эти мотивы, был Бело-Симион Файнаро (ивр.). В его работах еврейские буквы и другие символы были использованы в качестве основы для создания объектов, имеющих метафизическое и религиозное значение. В работе «Там» (1996), например, Файнаро создал замкнутую структуру, окна которой изображены в форме буквы иврита «ש» — «шин». Другая работа — модель синагоги (1997) с фиксированными окнами в форме букв «א — ז» — «алеф — заин», представляющих дни сотворения мира[56].

В Израиле памятники созданы, в основном, для увековечивания памяти множества различных событий в истории государства, особенно Холокоста и войн Израиля. Памятники выставлены в общественно доступных местах и являются популярным выражением искусства соответствующего периода. Первым крупным памятником в Эрец-Исраэль была статуя «Рычащего льва» (ивр.), созданная скульптором Авраамом Мельниковым и установленная в Тель-Хай. Большие размеры памятника и государственное финансирование работы были новаторством в израильском искусстве того времени. Являясь произведением скульптуры, памятник относится к «ханаанейскому» искусству раннего периода.

Памятники, возведённые в Израиле в начале 50-х годов XX века, многие из которых были созданы в честь воинов, падших в войнах за освобождение и независимость страны, характеризуются образностью композиций и «элегическим» тоном, вызывающим сионистские настроения у израильской общественности[59]. Памятники спроектированы как театральное пространство. Общепринятая модель памятника состоит из каменной или мраморной стены, обратная сторона которой не используется. На внешней стороне выгравированы имена погибших, а вместе с ними барельефное изображение раненого солдата или аллегорическое изображение, как, например, изображение льва. Основные памятники были размещены в направлении, перпендикулярном к пространству церемонии, в целях обеспечения качественного обзора со всех сторон[60].

Один из известных создателей скульптурных памятников в первые десятилетия после создания государства Израиль — Натан Рапопорт, репатриировавшийся в Израиль в 1950 году после пребывания в Варшавском гетто. Многие памятники, воздвигнутые Рапопортом и посвящённые событиям, связанным с войнами за независимость, являются скульптурными произведениями экспрессивного характера, привнесённого из нео-классического стиля. Центральное место в памятнике Рапопорта «Площадь в Варшавском гетто», установленном в Яд ва-Шем (1971), занимает барельеф под названием «Прогулка к смерти», где изображена группа евреев, несущих свиток Торы. Слева Рапопорт установил копию памятника, созданную для варшавского гетто. Таким образом, был создан рассказ о Холокосте, подчеркивающий не только трагедию, но и героическое мужество её жертв.

В проектировании памятников учитываются различия между восприятием памяти, характерным для различных периодов. В то время как памятник „Молодому защитнику“, например, относится к группе героических памятников, созданных Натаном Рапопортом в Яд-Мордехай (1951) или на юге (1953), в которых заметен значительный опыт выражения идеологических и социальных аспектов искусства, и являющихся выражением сообщества, в кибуце Арци были установлены памятники интимного характера или посвящённые природе, такие, как например, „Мать и дитя“, созданный Ханой Орлов (ивр.) и установленный в кибуце Эйн-Гев (1952); или памятники Йехиэля Шеми (ивр.) в кибуце Ха-Солелим (1954). Эти произведения отражают внутренний мир личности и являются образцами образцами абстрактного искусства[61].

В отличие от примеров образного искусства, в скульптурных памятниках, созданных в 50-е годы, заметно преобладание абстрактной тенденции. В центре «Памятника летчикам» (50-е годы), созданного Беньямином Таммузом и Абой Эльханнани (ивр.) в Парке Независимости в Тель-Авив — Яффо, — изображение птицы, парящей над обрывом тель-авивского пляжа. Тенденции абстрактного искусства можно найти и в работах Давида Паломбо (ивр.), который создал рельефы и памятники для зданий государственных учреждений, таких как Кнессет, или Яд ва-Шем; и во многих других произведениях, таких, как памятник Шломо Бен-Йосефу (1957), созданный Ицхаком Данцигером в Рош-Пине. Тем не менее, поворотный пик тенденции образного изображения выражен в Памятнике «Бригаде Негева» (1963—1968), созданном Дани Караваном на окраине города Беэр-Шева. Памятник выполнен в виде образных элементов с внутренним метафорическим смыслом, композиция которых создаёт физический контакт между самим объектом и пустынным ландшафтом.

Сочетание символизма и абстракции заметно в «Скульптуре памяти жертв Холокоста», установленной на площади Рабина в Тель-Авиве (ранее «Площади царей Израиля»). Игаль Тумаркин (ивр.) при создании памятника использовал элемент символьной формы — перевёрнутую пирамиду, выполненную из стали, бетона и стекла. Хотя стеклянный памятник был призван отражать то, что происходит в городе[62], не отражая новое пространство, он гармонично вписался в общий пейзаж. Художественная трактовка, выраженная в произведении пирамидальной формы с треугольной основой, окрашенной в жёлтый цвет, символизирует «позор». Две совмещённые структуры образуют звезду Давида. Тумаркин образно сопоставлял памятник с «открытой тюремной камерой». В одном из интервью Тумаркин объяснял, что пирамида выступает и в качестве доказательства разрыва между идеологией и результатом порабощения: «Какой урок мы извлекли из строительства пирамид 4200 лет назад […] являются ли принудительный труд и смерть выражением свободы?»[63].

В 90-е годы ХХ-го века в Израиле началось строительство памятников зрелищного характера, не являющихся произведениями абстрактного искусства. В «Детском Мемориале» (1987), созданном Моше Сафди, или в мемориале «Вертолётная катастрофа», созданном в 2008 году, преобладает тенденция (наряду с символическими формами) использования различных методов, создающих эмоциональное восприятие.

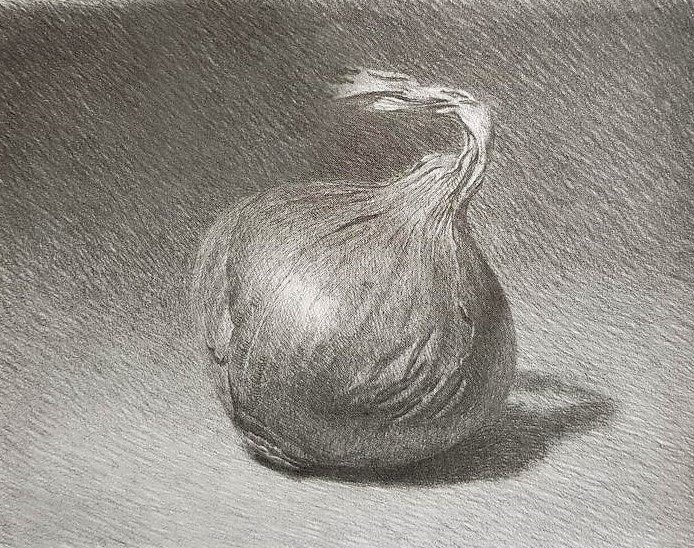

Израильское изобразительное скульптурное искусство характеризуется неоднозначным отношением к реалистичному изображению человеческого тела. Рождение израильской скульптуры совпало с бумом авангарда и модернизма в европейском искусстве, влияние которого проявилось и в скульптуре, созданной в период, начиная с 30-х годов XX века до настоящего времени. В сороковые годы в среде местных художников преобладала тенденция примитивизма, а с появлением «ханаанейской» скульптуры было высказано мнение, что развитие человеческого тела «носит характер ландшафта Эрец-Исраэль».

Пейзаж пустыни был центральной темой многих произведений искусства вплоть до 80-х годов XX века. Сокращалось использования камня и мрамора, а также традиционных методов обработки материала, таких как резьба, в то время как предпочтение отдавалось литью и сварке. Особенно это стало заметно в середине XX века, когда возросла популярность абстрактного искусства «Новых горизонтов». Однако, именно эти методы позволили художникам создавать скульптурные произведения монументальных масштабов, что ранее не было распространенным явлением в израильском искусстве.