Shana Tova u'Metuka!

! שנה טובה ומתוקה

Happy New Year !

Дом Искусств “Keshet Tslilim”

Хайфа, ул. Тель-Авив 11, 2-й этаж

Записаться также можно по телефону: Tel: 054 344 9543

https://www.ghenadiesontu.com/workshops/

#haifaart #israelart #bezalelart#кружкипорисованиювхайфе#домашнееобучение #Рисование#рисованиевхайфе #גנאדישונצו #ghenadiesontu#АртКласс #АртКлассДети #рисование #живопись#рисуйкаждыйдень #детскоетворчество#творчество #краски #аппликация#цветныекарандаши #учимрисовать#рисованиедетям #кружкидлядетей #хобби#образование #художественнаяшкола#художественноеобразование #учисьрисовать#детинашевсе #детицветыжизни#вселучшеедетям #рисунок #гуашь #акварелью

Contemporary architecture and ancient suggestions, the Louis Kahn's Hurva Synagogue project

Луис Кан (Louis Kahn) умер всего за несколько недель до очередной поездки в Иерусалим для обсуждения своего проекта реконструкции синагоги "Хурва" в еврейском квартале Старого Города. Многие эксперты считают этот проект величайшим нереализованным произведением 20 века.

Здание синагоги было построено в начале 18 века последователями Иегуды Хасида. В 1721 году оно было разрушено мусульманами и находилось в руинах более 140 лет, поэтому приобрело название "Хурва" (ивр. "руины"). В 1856 году османский султан дал разрешение на восстановление синагоги по проекту своего придворного архитектора Асада Эффенди. Строительством руководили британский меценат сэр Мозес Монтефиоре и раввин Шломо Залман Зореф, который был убит еще до начала строительства.

В 1864 году синагога все же была восстановлена и оставалась главной синагогой ашкеназов Иерусалима до разрушения её силами Арабского легиона в 1948 году. После Шестидневной Войны 1967 года, в результате которой Израиль получил восточную часть Иерусалима, снова возникла идея по восстановлению и заселению разрушенного еврейского квартала и реконструкции синагоги. Компанию по восстановлению "Хурва" возглавил праправнук Шломо Залмана Зорефа, известный адвокат, Яков Саломон. Он обратился к молодому тогда израильскому архитектору Раме Карми с просьбой разработать план строительства новой синагоги на ее прежнем месте. Карми от предложения отказался и рекомендовал пригласить для этой цели Луиса Кана - известного еврейского американского архитектора эстонского происхождения.

Луис Кан дал согласие на просьбу Саломона и вскоре приехал в Израиль для изучения места предполагаемого строительства. Архитектор настоял на походе в Иудейскую пустыню, так как хотел пережить опыт древних евреев, "которые пришли на эту землю, после 40 лет в пустыне". Так его группа посетила два отдаленных монастыря: Монастырь Святого Георгия в Вади Кельт и Мар Саба в долине Кидрон. По словам сестры Рамы Карми, Ады Карми-Меламид, когда Кан вышел из Мар Саба, он был под таким впечатлением, что "говорил, не останавливаясь, 12 часов".

Для Кана это была прекрасная возможность построить великий еврейский памятник в центре еврейского государства. Архитектор осознавал огромную ответственность этой задачи. В письме заказчикам в 1969 году он писал, что сильно взволнован тем фактом, что должен выразить дух истории и религии Иерусалима, что ощущает "вдохновение, которого он не чувствовал раньше". По мнению исследователя Кенета Ларсона, "Хурва была для Кана первая и, пожалуй, единственная возможность построить в контекст древних руин".

Руины в жизни Луиса Кана занимали особое место, вдохновляли его работу. Карьера Кана расцветает после того, как он в 1950-51 провел несколько месяцев в Риме, где изучал древнюю архитектуру. Кан стремился воплотить в синагоге и других своих проектах силу и монументализм руин через простые геометрические формы. Благодаря такому подходу, позже исследователи будут сравнивать проект синагоги "Хурва" с сооружениями древних миров: с зиккуратами древней Месопотамии, египетским Храмом в Луксоре, постройками характерными для сефардских евреев из Центральной Азии.

История синагоги "Хурва" - это судьба руин, так как большую часть своей жизни здание было разрушено. Также как и реконструкция башен Всемирного Торгового Центра, проект восстановления синагоги поднимает вопрос о строительстве на территориях, которые в значительной степени определены историей своего уничтожения.

По замечанию Карми: "Мы должны помнить, что Луис Кан увидел еврейский квартал разрушенным. Ничего не было, были только следы". Поэтому Луис Кан в проекте синагоги создает руины, но не в буквальном смысле. Он демонстрирует специфический способ своего мышления: "В каждой вещи, что природа создает, она записывает, как это было сделано. Гора - это запись, как гора была сделана. Человек - это то, как человек был сделан". Руины для Кана приобретают определенный смысл записи, следа разрушения здания природой и историей. Архитектор стремится записать в архитектуре то, "как" она была сделана, здание для Кана изначально является руиной, человеческим следом.

За время между 1968 и 1973 годами Кан представил три варианта реконструкции. В каждом из них Кан предлагал строить новое здание не на месте старого, а рядом с ним; оставить развалины в качестве мемориального сада. Между синагогой и Стеной плача Кан хотел создать грандиозный променад "дорогу Пророков" ("the Route of the Prophets").

Размышляя о проекте синагоги, Кан делает свое знаменитое и загадочное замечание о руинах и свете: "Я думал о красоте руины… вещи, которая не живет после… так я думал обернуть руины вокруг здания, понять руины как оболочку здания… так, что вы можете смотреть сквозь стены будто бы случайно... я чувствовал, что это было ответом на проблему яркого, прямого света".

Так, по его мнению, синагога должна состоять из двух зданий: "наружное будет поглощать свет и тепло солнца, а внутреннее будет давать эффект отдельного, но связанного с внешним миром пространства". Наружная структура-оболочка оборачивает внутреннее здание. Она представляет собой 16 опор-пилонов высотой 12 метров из блоков иерусалимского камня. Внутренняя структура представляет собой четыре огромные колонны из железобетона и установленные на них перевернутые пирамиды, которые поддерживают крышу здания. Внутри колонн находятся ниши для индивидуальной молитвы или медитации. Таким образом, внешние пилоны функционируют как контейнер, а внутренние колонны как содержимое.

Проект синагоги "Хурва" так и не был реализован. Это произошло по стечению разных обстоятельств: политические причины, чиновничье бездействие, эстетическая робость. Искусствовед Михаил Левин из Израильского Технологического Института утверждает, что "проект был слишком радикален для правительственных чиновников, в результате чего мы пропустили один из великих шедевров 20-го века".

Мэр Иерусалима, Тедди Коллек, когда увидел масштабы задумки Кана, заявил: "Следует ли нам в еврейском квартале иметь здание, которое конкурирует с Мечетью и Гробом Господнем, должны ли мы строить здание, которое будет важнее Стены Плача?" Даже Яков Саломон, который работал над осуществлением проекта Кана до самой своей смерти в 1980 году, был обеспокоен: в 1968 году он писал Кану, что здание вышло "гораздо больше, чем я себе представлял".

Защитники проекта Луиса Кана считали, что Иерусалиму не была нужна еще одна синагога, там, где их и так слишком много. Они говорили, что городу необходимо здание для общественной активности. Знаменитый архитектор Моше Софди также поддерживал проект Кана. Он утверждал, что "абсурдно реконструировать Хурва как ни в чем не бывало. Если у нас есть желание восстановить синагогу, нужно иметь мужество позволить великому архитектору сделать это".

В 1977 году на месте разрушенной синагоги была возведена 16-метровая каменная арка, которая обозначала пространство, где когда-то находилась синагога "Хурва". А в 2000 году правительством был утверждён план строительства на этом месте новой синагоги, которая должна была стать копией здания 19 века. Новая синагога в неовизантийском стиле была открыта 15 марта 2010 года.

Source: http://architime.ru

Biblical Zionism in Bezalel Art

by Dalia Manor

SURPRISING AS IT MAY SOUND, the visual art that has developed in Jewish Palestine and in Israel has drawn its inspiration from the Bible only on a limited scale. In recent years, some biblical themes have been taken by artists as metaphor in response to events in contemporary life. 1 But, as a whole, the bible has been far less significant for Israeli art then one would expect, especially when comparing the field to literature. The art of Bezalel, whose school and workshops were established in Jerusalem in 1906, is a special case however. This article will discuss the role and meaning of the use of biblical themes in the art of this institution, the founding of which is commonly regarded as marking the beginning of Israeli art.

The works produced in the Bezalel School of Art and Crafts in Jerusalem during its first phase (1906-1929) are usually classified according to the material and technique employed in their making. In analyzing the objects, greater emphasis is given to questions of style, whereas the iconography is discussed in broad generalizations or linked with stylistic aspects. 2 Setting aside questions of style or function, however, the works produced at Bezalel reveal that biblical themes played a considerable part; but this is by no means obvious. With regards to activity in the field of Jewish art in Europe at the time of Bezalel's foundation, and the later developments in Jewish art in Eretz Yisrael since the 1920s, it seems fairly clear that the recurrence of biblical subjects in Bezalel art is in fact exceptional. Since the iconography of Bezalel has been very little explored, this phenomenon has been overlooked. 3 This is partly due to the nature of Bezalel products, which are classified as decorative art and handicrafts, and are thus traditionally discussed in terms of form and quality of execution, rather than in terms of subject matter. Since Bezalel was not merely an art school accompanied by workshops, but rather an organized enterprise that aimed at national and cultural goals, the study of the subject matter of its artistic products may offer a further insight into the purpose and meaning of these works and of the Bezalel project in general.

The analysis of the subject matter in Bezalel art is based on the most comprehensive survey so far of Bezalel works--the exhibition held at the Israel Museum in 1983 and its accompanying catalogue, 4 which shows that biblical themes are prominent in figurative works. With the exclusion of portraits, of all the figure representations, biblical figures comprise about half, and biblical themes exceed by far other historic and Jewish themes. Although the themes are varied and some occur only rarely, certain tendencies emerge in the choice of biblical subjects:

1. There is an emphasis on figures that represent leadership, heroism, and salvation; e.g., Moses, David, Samson, Judith and Esther.

2. There are numerous scenes of exile and redemption: by the waters of Babylon, the exodus from Egypt, the prophet Elijah who proclaims the redemption and prophecies of the last days, particularly those describing ideal peace. Especially prominent in this category is the image of the two spies carrying the cluster of grapes, thus expressing their view of the land of milk and honey. One may also add to this group images of Adam and Eve in Paradise.

3. There is a particular attraction to the use of romantic pastorals in "oriental" scenery--most often the meeting of Rebecca and Eliezer at the well, Jacob and Rachel, and the figure of Ruth. The ideal romantic love is of course depicted via the Song of Songs.

Generally speaking, no conflict, war, disaster or negative aspect of biblical life are depicted, with the exception of the selling of Joseph and the Expulsion from Eden, both of which are rare. Even the depiction of the Akedah (The Binding of Isaac) is rare. Also rare are themes that involve contact between humankind and the divine, such as meeting with angels..

The Architect of the Tabernacle

In Ex. xxxi. 1-6, the chief architect of the Tabernacle. Elsewhere in the Bible the name occurs only in the genealogical lists of the Book of Chronicles, but according to cuneiform inscriptions a variant form of the same, "Ẓil-BêI," was borne by a king of Gaza who was a contemporary of Hezekiah and Manasseh. Apparently it means "in the shadow [protection] of El." Bezalel is described in the genealogical lists as the son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah (I Chron. ii. 18, 19, 20, 50). He was said to be highly gifted as a workman, showing great skill and originality in engraving precious metals and stones and in wood-carving. He was also a master-workman, having many apprentices under him whom he instructed in the arts (Ex. xxxv. 30-35). According to the narrative in Exodus, he was definitely called and endowed to direct the construction of the tent of meeting and its sacred furniture, and also to prepare the priests' garments and the oil and incense required for the service.

—In Rabbinical Literature:

The rabbinical tradition relates that when God determined to appoint Bezalel architect of the desert Tabernacle, He asked Moses whether the choice were agreeable to him, and received the reply: "Lord, if he is acceptable to Thee, surely he must be so to me!" At God's command, however, the choice was referred to the people for approval and was indorsed by them. Moses thereupon commanded Bezalel to set about making the Tabernacle, the holy Ark, and the sacred utensils. It is to be noted, however, that Moses mentioned these in somewhat inverted order, putting the Tabernacle last (compare Ex. xxv. 10, xxvi. 1 et seq., with Ex. xxxi. 1-10). Bezalel sagely suggested to him that men usually build the house first and afterward provide the furnishings; but that, inasmuch as Moses had ordered the Tabernacle to be built last, there was probably some mistake and God's command must have run differently. Moses was so pleased with this acuteness that he complimented Bezalel by saying that, true to his name, he must have dwelt "in the very shadow of God" (Hebr., "beẓel El"). Compare also Philo, "Leg. Alleg." iii. 31.

Bezalel possessed such great wisdom that he could combine those letters of the alphabet with which heaven and earth were created; this being the meaning of the statement (Ex. xxxi. 3): "I have filled him . . . with wisdom and knowledge," which were the implements by means of which God created the world, as stated in Prov. iii. 19, 20 (Ber. 55a). By virtue of his profound wisdom, Bezalel succeeded in erecting a sanctuary which seemed a fit abiding-place for God, who is so exalted in time and space (Ex. R. xxxiv. 1; Num. R. xii. 3; Midr. Teh. xci.). The candlestick of the sanctuary was of so complicated a nature that Moses could not comprehend it, although God twice showed him a heavenly model; but when he described it to Bezalel, the latter understood immediately, and made it at once; whereupon Moses expressed his admiration for the quick wisdom of Bezalel, saying again that he must have been "in the shadow of God" (Hebr., "beẓel El") when the heavenly models were shown him (Num. R. xv. 10; compare Ex. R. 1. 2; Ber. l.c.). Bezalel is said to have been only thirteen years of age when he accomplished his great work (Sanh. 69b); he owed his wisdom to the merits of pious parents; his grandfather being Hur and his grandmother Miriam, he was thus a grand-nephew of Moses (Ex. R. xlviii. 3, 4). Compare Ark in Rabbinical Literature.

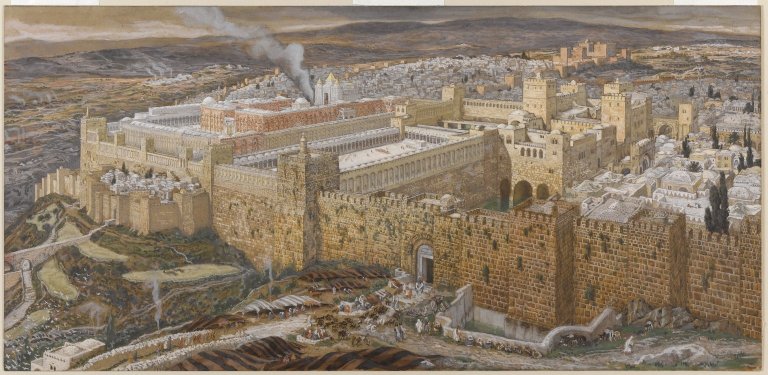

Second Themple

The Second Temple (Hebrew: בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ הַשֵּׁנִי, Beit HaMikdash HaSheni) was the Jewish Holy Temple which stood on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem during the Second Temple period, between 516 BCE and 70 CE. According to Judeo-Christian tradition, it replaced Solomon's Temple (the First Temple), which was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE, when Jerusalem was conquered and part of the population of the Kingdom of Judah was taken into exile to Babylon.

Jewish eschatology includes a belief that the Second Temple will be replaced by a future Third Temple.

According to the Bible, when the Jewish exiles returned to Jerusalem following a decree from Cyrus the Great (Ezra 1:1–4, 2 Chron 36:22–23), construction started at the original site of Solomon's Temple. After a relatively brief halt due to opposition from peoples who had filled the vacuum during the Jewish captivity (Ezra 4), work resumed ca. 521 BCE under Darius the Great (Ezra 5) and was completed during the sixth year of his reign (ca. 516 BCE), with the temple dedication taking place the following year.

The events take place in the second half of the 5th century BCE. Listed together with the Book of Ezra as Ezra-Nehemiah, it represents the final chapter in the historical narrative of the Hebrew Bible.[1]

The original core of the book, the first-person memoir, may have been combined with the core of the Book of Ezra around 400 BCE. Further editing probably continued into the Hellenistic era.[3]

The book tells how Nehemiah, at the court of the king in Susa, is informed that Jerusalem is without walls and resolves to restore them. The king appoints him as governor of the province Yehud Medinata and he travels to Jerusalem. There he rebuilds the walls, despite the opposition of Israel's enemies, and reforms the community in conformity with the law of Moses. After 12 years in Jerusalem, he returns to Susa but subsequently revisits Jerusalem. He finds that the Israelites have been backsliding and taking non-Jewish wives, and he stays in Jerusalem to enforce the Law.

Based on the biblical account, after the return from Babylonian captivity, arrangements were immediately made to reorganize the desolated Yehud Province after the demise of the Kingdom of Judah seventy years earlier. The body of pilgrims, forming a band of 42,360,[4] having completed the long and dreary journey of some four months, from the banks of the Euphrates to Jerusalem, were animated in all their proceedings by a strong religious impulse, and therefore one of their first concerns was to restore their ancient house of worship by rebuilding their destroyed Temple[5] and reinstituting the sacrificial rituals known as the korbanot.

On the invitation of Zerubbabel, the governor, who showed them a remarkable example of liberality by contributing personally 1,000 golden darics, besides other gifts, the people poured their gifts into the sacred treasury with great enthusiasm.[6] First they erected and dedicated the altar of God on the exact spot where it had formerly stood, and they then cleared away the charred heaps of debris which occupied the site of the old temple; and in the second month of the second year (535 BCE), amid great public excitement and rejoicing, the foundations of the Second Temple were laid. A wide interest was felt in this great movement, although it was regarded with mixed feelings by the spectators (Haggai 2:3, Zechariah 4:10</ref>).[5]

The Samaritans made proposals for co-operation in the work. Zerubbabel and the elders, however, declined all such cooperation, feeling that the Jews must build the Temple without help. Immediately evil reports were spread regarding the Jews. According to Ezra 4:5, the Samaritans sought to "frustrate their purpose" and sent messengers to Ecbatana and Susa, with the result that the work was suspended.[5]

Seven years later, Cyrus the Great, who allowed the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple, died (2 Chronicles 36:22–23) and was succeeded by his son Cambyses. On his death, the "false Smerdis," an impostor, occupied the throne for some seven or eight months, and then Darius became king (522 BCE). In the second year of his rule the work of rebuilding the temple was resumed and carried forward to its completion (Ezra 5:6–6:15), under the stimulus of the earnest counsels and admonitions of the prophets Haggai and Zechariah. It was ready for consecration in the spring of 516 BCE, more than twenty years after the return from captivity. The Temple was completed on the third day of the month Adar, in the sixth year of the reign of Darius, amid great rejoicings on the part of all the people (Ezra 6:15,16), although it was evident that the Jews were no longer an independent people, but were subject to a foreign power. The Book of Haggai includes a prediction that the glory of the second temple would be greater than that of the first (Haggai 2:9).[5]

Some of the original artifacts from the Temple of Solomon are not mentioned in the sources after its destruction in 597 BCE, and are presumed lost. The Second Temple lacked the following holy articles:

Israeli Art

Part of what makes the art scene in Israel so unique is that the country blends so many varying influences from all over the Jewish world.

BY MJL STAFF

Though the modern State of Israel has officially been independent only since 1948, its unique blend of dynamic arts and different cultural traditions has been around for some time longer. Part of what makes the art scene in Israel so unique is that the country blends so many varying influences from all over the Jewish world. In the case of folk arts, for example, a wide range of crafts can be found flourishing–from Yemenite-style jewelry making to the embroidery and other needle crafts of the Eastern European Jews. Over the last half-century, as artisans have mixed and mingled and learned from one another, a certain “Israeli” style of folk art has emerged, reflecting all of the cultures who make up the modern state.

In the fine arts, there has also been a desire to create an “Israeli” art. From the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when significant numbers of Jews began fleeing Europe and settling in the Land of Israel with Zionistic dreams, the fine arts have occupied a prominent place in Israeli life. Artist Boris Schatz came to Jerusalem in order to establish the Bezalel School–named for the Biblical figure chosen by God to create the first tabernacle. A university-level academy known today as the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, the flourishing of the school typifies the country’s support of its artists.

Unlike the United States, where the virtue of public art continues to be debated, the Israeli government makes clear its support of visual artists and their contributions to society. In Israel, the role of public art helps to express and define the concerns of a common, yet diverse, culture. In a country that struggles daily to protect its inhabitants, art is considered to be a necessity, rather than a luxury. Perhaps it is the distinct Israeli-style “live for today” philosophy that makes the appreciation of art more vivid than in other, “safer” countries.

Not that Israel’s artists have always had an easy time defining themselves in relation to the rest of the art world. Early Israeli painters like Nahum Gutman tried to create a unique “Hebrew” style of art–capturing the excitement of establishing a Zionist state–while maintaining his influences from Modern European art. Other great Israeli artists such as Reuven Rubin had to leave Israel for periods of their life in order to receive the recognition that they desired; Rubin’s first major exhibit was held in the United States, thanks to his friend, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz.

Not all successful Israeli artists have portrayed Jewish or Zionist themes in their work. One of Israel’s best-known artists, for example, Yaacov Agam, is known for his unique expression of optical art. Indeed, as life in Israel became more established, the diversity of Israeli artists increased. As Israeli artists became accepted into the international art scene, their work took on the various styles and aesthetic approaches reflected in the wider art world.

Just as the politics of two Israelis can be as far apart on the spectrum as imaginable, so are the political ideologies of its artists, whose works might include everything from anti-war statements to paintings of national pride. Israeli art has matured to express the range of opinions and emotions circling in Israeli life; therefore, there is no one style, ideology or medium that defines an Israeli artist today.

But what each Israeli artist has in common is that they are fortunate to come from a culture that values the work of artists and continues to support creation of the arts as an integral part of its unique social fabric.

© Faces Media