This year’s sale of Important Judaica features an outstanding selection of rare medieval Hebrew manuscripts and printed books. Highlights include a magnificently Illuminated Medieval Hebrew Bible from Spain (3,500,0000–5,000,000 USD), a newly discovered 13th-century micrographic Hebrew Bible from France (400,000–600,000 USD) and a previously unknown copy of the first edition of the German-Rite Daily Prayer Book accompanied by a unicum Haggadah, printed in Venice, 1519–20 (250,000–350,000 USD). In addition, this sale will include splendid textiles and a fine selection of ritual silver and metalwork, most notably a group of rare 18th-century silver book bindings, including examples from Rome, Venice, Hamburg and Altona, from the estate of Jack Lunzer, Custodian of the Valmadonna Trust Library. The paintings section is distinguished by a magnificent oil of Moses on Mount Sinai by Jean-Léon Gérôme (100,000–150,000 USD) and three works by Arthur Szyk, currently the subject of an important exhibition at the New York Historical Society.

The painting ‘Salvator Mundi’ by Leonardo da Vinci at Christie’s

After 19 minutes of dueling, with four bidders on the telephone and one in the room, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi” sold on Wednesday night for $450.3 million with fees, shattering the high for any work of art sold at auction. It far surpassed Picasso’s “Women of Algiers,” which fetched $179.4 million at Christie’s in May 2015. The buyer was not immediately disclosed.

There were gasps throughout the sale, as the bids climbed by tens of millions up to $225 million, by fives up to $260 million, and then by twos. As the bidding slowed, and a buyer pondered the next multi-million-dollar increment, Jussi Pylkkanen, the auctioneer, said, “It’s an historic moment; we’ll wait.”

Toward the end, Alex Rotter, Christie’s co-chairman of postwar and contemporary art, who represented a buyer on the phone, made two big jumps to shake off one last rival bid from Francis de Poortere, Christie’s head of old master paintings.

The price is all the more remarkable at a time when the old masters market is contracting, because of limited supply and collectors’ penchant for contemporary art.

And to critics, the astronomical sale attests to something else — the degree to which salesmanship has come to drive and dominate the conversation about art and its value. Some art experts pointed to the painting’s damaged condition and its questionable authenticity.

“This was a thumping epic triumph of branding and desire over connoisseurship and reality,” said Todd Levin, a New York art adviser.

Christie’s marketing campaign was perhaps unprecedented in the art world; it was the first time the auction house went so far as to enlist an outside agency to advertise the work. Christie’s also released a videothat included top executives pitching the painting to Hong Kong clients as “the holy grail of our business” and likening it to “the discovery of a new planet.” Christie’s called the work “the Last da Vinci,” the only known painting by the Renaissance master still in a private collection (some 15 others are in museums).

“It’s been a brilliant marketing campaign,” said Alan Hobart, director of the Pyms Gallery in London, who has acquired museum-quality artworks across a range of historical periods for the British businessman and collector Graham Kirkham. “This is going to be the future.”

There was a palpable air of anticipation at Christie’s Rockefeller Center headquarters as the art market’s major players filed into the sales room. The capacity crowd included top dealers like Larry Gagosian, David Zwirner and Marc Payot of Hauser & Wirth. Major collectors had traveled here for the sale, among them Eli Broad and Michael Ovitz from Los Angeles; Martin Margulies from Miami; and Stefan Edlis from Chicago. Christie’s had produced special red paddles for those bidding on the Leonardo, and many of its specialists taking bids on the phone wore elegant black.

Earlier, 27,000 people had lined up at pre-auction viewings in Hong Kong, London, San Francisco and New York to glimpse the painting of Christ as “Savior of the World.” Members of the public — indeed, even many cognoscenti — cared little if at all whether the painting might have been executed in part by studio assistants; whether Leonardo had actually made the work himself; or how much of the canvas had been repainted and restored. They just wanted to see a masterwork that dates from about 1500 and was rediscovered in 2005.

“There is extraordinary consensus it is by Leonardo,” said Nicholas Hall, the former co-chairman of old master paintings at Christie’s, who now runs his own Manhattan gallery. “This is the most important old master painting to have been sold at auction in my lifetime.”

That is the kind of name-brand appeal that Christie’s was presumably banking on by placing the painting in its high-profile contemporary art sale, rather than in its less sexy annual old master auction, where it technically belongs. To some extent, the auction house succeeded with the painting even before the sale, having secured a guaranteed $100 million bid from an unidentified third party. It is the 12th artwork to break the $100 million mark at auction, and a new high for any old master at auction, surpassing Rubens’s “Massacre of the Innocents,” which sold for $76.7 million in 2002 (or more than $105 million, adjusted for inflation).

But many art experts argue that Christie’s used marketing window dressing to mask the baggage that comes with the Leonardo, from its compromised condition to its complicated buying history and said that the auction house put the artwork in a contemporary sale to circumvent the scrutiny of old masters experts, many of whom have questioned the painting’s authenticity and condition.

“The composition doesn’t come from Leonardo,” said Jacques Franck, a Paris-based art historian and Leonardo specialist. “He preferred twisted movement. It’s a good studio work with a little Leonardo at best, and it’s very damaged.”

“It’s been called ‘the male Mona Lisa,’” he said, “but it doesn’t look like it at all.” Mr. Franck said he has examined the Mona Lisa out of its frame five times.

Luke Syson, curator of the 2011 National Gallery exhibition in London that featured the painting, said in his catalog essay that “the picture has suffered.” While both hands are well preserved, he said, the painting was “aggressively over cleaned,” resulting in abrasion of the whole surface, “especially in the face and hair of Christ.”

Christie’s maintains that it was upfront about the much-restored, damaged condition of the oil-on-panel, which shows Christ with his right hand raised in blessing and his left holding a crystal orb.

But Christie’s was also slow to release an official condition report and its authenticity warranty on the Leonardo runs out in five years, as it does on all lots bought at its auctions, according to the small print in the back of its sale catalog.

The auction house has also played down the painting’s volatile sales history.

The artwork has been the subject of legal disputes and amassed a price history that ranges from less than $10,000 in 2005, when it was spotted at an estate auction, to $200 million when it was first offered for sale by a consortium of three dealers in 2012. But no institution besides the Dallas Museum of Art, which in 2012 made an undisclosed offer on the painting, showed public interest in buying it. Finally, in 2013, Sotheby’s sold it privately for $80 million to Yves Bouvier, a Swiss art dealer and businessman. Soon afterward, he sold it for $127.5 million, to the family trust of the Russian billionaire collector Dmitry E. Rybolovlev. Mr. Rybolovlev’s family trust was the seller on Wednesday night.

There was speculation that Liu Yiqian, a Chinese billionaire and co-founder with his wife of the Long Museum in Shanghai, may have been among the bidders. In recent years, the former taxi-driver-turned-power collector has become known for his splashy, record-breaking art purchases, including an Amedeo Modigliani nude painting for $170.4 million at a Christie’s auction in 2015. But in a message sent to a reporter via WeChat, a Chinese messaging app, Mr. Liu said he was not among the bidders for the Leonardo.

On Thursday morning, soon after the final sale was announced, Mr. Liu posted a message on his WeChat social media feed. “Da Vinci’s Savior sold for 400 million USD, congratulations to the buyer,” he wrote. “Feeling kind of defeated right now.”

By ROBIN POGREBIN and SCOTT REYBURN

Biblical Zionism in Bezalel Art

by Dalia Manor

SURPRISING AS IT MAY SOUND, the visual art that has developed in Jewish Palestine and in Israel has drawn its inspiration from the Bible only on a limited scale. In recent years, some biblical themes have been taken by artists as metaphor in response to events in contemporary life. 1 But, as a whole, the bible has been far less significant for Israeli art then one would expect, especially when comparing the field to literature. The art of Bezalel, whose school and workshops were established in Jerusalem in 1906, is a special case however. This article will discuss the role and meaning of the use of biblical themes in the art of this institution, the founding of which is commonly regarded as marking the beginning of Israeli art.

The works produced in the Bezalel School of Art and Crafts in Jerusalem during its first phase (1906-1929) are usually classified according to the material and technique employed in their making. In analyzing the objects, greater emphasis is given to questions of style, whereas the iconography is discussed in broad generalizations or linked with stylistic aspects. 2 Setting aside questions of style or function, however, the works produced at Bezalel reveal that biblical themes played a considerable part; but this is by no means obvious. With regards to activity in the field of Jewish art in Europe at the time of Bezalel's foundation, and the later developments in Jewish art in Eretz Yisrael since the 1920s, it seems fairly clear that the recurrence of biblical subjects in Bezalel art is in fact exceptional. Since the iconography of Bezalel has been very little explored, this phenomenon has been overlooked. 3 This is partly due to the nature of Bezalel products, which are classified as decorative art and handicrafts, and are thus traditionally discussed in terms of form and quality of execution, rather than in terms of subject matter. Since Bezalel was not merely an art school accompanied by workshops, but rather an organized enterprise that aimed at national and cultural goals, the study of the subject matter of its artistic products may offer a further insight into the purpose and meaning of these works and of the Bezalel project in general.

The analysis of the subject matter in Bezalel art is based on the most comprehensive survey so far of Bezalel works--the exhibition held at the Israel Museum in 1983 and its accompanying catalogue, 4 which shows that biblical themes are prominent in figurative works. With the exclusion of portraits, of all the figure representations, biblical figures comprise about half, and biblical themes exceed by far other historic and Jewish themes. Although the themes are varied and some occur only rarely, certain tendencies emerge in the choice of biblical subjects:

1. There is an emphasis on figures that represent leadership, heroism, and salvation; e.g., Moses, David, Samson, Judith and Esther.

2. There are numerous scenes of exile and redemption: by the waters of Babylon, the exodus from Egypt, the prophet Elijah who proclaims the redemption and prophecies of the last days, particularly those describing ideal peace. Especially prominent in this category is the image of the two spies carrying the cluster of grapes, thus expressing their view of the land of milk and honey. One may also add to this group images of Adam and Eve in Paradise.

3. There is a particular attraction to the use of romantic pastorals in "oriental" scenery--most often the meeting of Rebecca and Eliezer at the well, Jacob and Rachel, and the figure of Ruth. The ideal romantic love is of course depicted via the Song of Songs.

Generally speaking, no conflict, war, disaster or negative aspect of biblical life are depicted, with the exception of the selling of Joseph and the Expulsion from Eden, both of which are rare. Even the depiction of the Akedah (The Binding of Isaac) is rare. Also rare are themes that involve contact between humankind and the divine, such as meeting with angels..

The Architect of the Tabernacle

In Ex. xxxi. 1-6, the chief architect of the Tabernacle. Elsewhere in the Bible the name occurs only in the genealogical lists of the Book of Chronicles, but according to cuneiform inscriptions a variant form of the same, "Ẓil-BêI," was borne by a king of Gaza who was a contemporary of Hezekiah and Manasseh. Apparently it means "in the shadow [protection] of El." Bezalel is described in the genealogical lists as the son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah (I Chron. ii. 18, 19, 20, 50). He was said to be highly gifted as a workman, showing great skill and originality in engraving precious metals and stones and in wood-carving. He was also a master-workman, having many apprentices under him whom he instructed in the arts (Ex. xxxv. 30-35). According to the narrative in Exodus, he was definitely called and endowed to direct the construction of the tent of meeting and its sacred furniture, and also to prepare the priests' garments and the oil and incense required for the service.

—In Rabbinical Literature:

The rabbinical tradition relates that when God determined to appoint Bezalel architect of the desert Tabernacle, He asked Moses whether the choice were agreeable to him, and received the reply: "Lord, if he is acceptable to Thee, surely he must be so to me!" At God's command, however, the choice was referred to the people for approval and was indorsed by them. Moses thereupon commanded Bezalel to set about making the Tabernacle, the holy Ark, and the sacred utensils. It is to be noted, however, that Moses mentioned these in somewhat inverted order, putting the Tabernacle last (compare Ex. xxv. 10, xxvi. 1 et seq., with Ex. xxxi. 1-10). Bezalel sagely suggested to him that men usually build the house first and afterward provide the furnishings; but that, inasmuch as Moses had ordered the Tabernacle to be built last, there was probably some mistake and God's command must have run differently. Moses was so pleased with this acuteness that he complimented Bezalel by saying that, true to his name, he must have dwelt "in the very shadow of God" (Hebr., "beẓel El"). Compare also Philo, "Leg. Alleg." iii. 31.

Bezalel possessed such great wisdom that he could combine those letters of the alphabet with which heaven and earth were created; this being the meaning of the statement (Ex. xxxi. 3): "I have filled him . . . with wisdom and knowledge," which were the implements by means of which God created the world, as stated in Prov. iii. 19, 20 (Ber. 55a). By virtue of his profound wisdom, Bezalel succeeded in erecting a sanctuary which seemed a fit abiding-place for God, who is so exalted in time and space (Ex. R. xxxiv. 1; Num. R. xii. 3; Midr. Teh. xci.). The candlestick of the sanctuary was of so complicated a nature that Moses could not comprehend it, although God twice showed him a heavenly model; but when he described it to Bezalel, the latter understood immediately, and made it at once; whereupon Moses expressed his admiration for the quick wisdom of Bezalel, saying again that he must have been "in the shadow of God" (Hebr., "beẓel El") when the heavenly models were shown him (Num. R. xv. 10; compare Ex. R. 1. 2; Ber. l.c.). Bezalel is said to have been only thirteen years of age when he accomplished his great work (Sanh. 69b); he owed his wisdom to the merits of pious parents; his grandfather being Hur and his grandmother Miriam, he was thus a grand-nephew of Moses (Ex. R. xlviii. 3, 4). Compare Ark in Rabbinical Literature.

Уроки рисования и живописи в Хайфе

Дорогие друзья, мы приглашаем детей и взрослых на занятия по рисунку и живописи в Хайфе.

Программа обучения рисованию рассчитана как на желающих начать рисовать “с нуля”, так и на тех, кто хочет закрепить ранее приобретенные навыки.

На обучение рисованию принимаем всех желающих – детей, подростков, и взрослых. Пройдя наши художественные курсы живописи и рисования, вы очень быстро наберетесь мастерства для создания своих неповторимых авторских работ.

Техники

Живопись: акварель, акрил, гуашь, масло

Рисунок: графика, пастель, эстамп, монотипия

Керамика: лепка, мозаика, полимерная глина

Время занятий

4 - 7 лет: понедельник-среда: 15:00 - 16:30,

воскресенье: 15:00 - 16:30.

8 - 10 лет: вторник-четверг: 15:00 - 16:30, 17:00 - 18:30, воскресенье: 17:00 - 18:30,

11 - 15 лет: понедельник-среда: 17:00 - 18:30,

16 лет и старше: воскресенье: 9:00 - 11:15; 18:30 -20:45, понедельник: 18:30 - 20:45.

воскресенье: 11:00 - 13:00;

вторник: 18:30 - 20:30;

среда: 10:00 - 13:00;

пятница: 10:00 - 12:00.

Интенсивность и длительность занятий: 1,5 часа, 2 раза в неделю.

Цена курса

Групповые занятия для детей 5 - 15 лет - 250 шек./месяц, это 8 уроков по 1,5 часа = 12 часов в месяц.

Групповые занятия для взрослых от 16 лет и старше - 300 шек./месяц, это 4 уроков по 2 часа 15 мин. = 9 часов в месяц.

Индивидуальные занятия для детей и взрослых от 16 лет и старше - 100 шекелей в час. Минимальный пакет из 5 уроков стоит 500 шекелей. Занятия проводятся в удобное для вас время, утром или вечером.

Свяжитесь с нами!

Записаться также можно по тел.: 054 344 9543

https://www.ghenadiesontu.com/workshops/

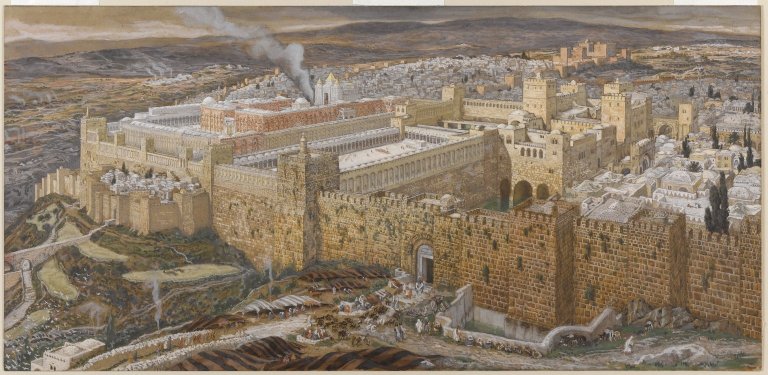

Second Themple

The Second Temple (Hebrew: בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ הַשֵּׁנִי, Beit HaMikdash HaSheni) was the Jewish Holy Temple which stood on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem during the Second Temple period, between 516 BCE and 70 CE. According to Judeo-Christian tradition, it replaced Solomon's Temple (the First Temple), which was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE, when Jerusalem was conquered and part of the population of the Kingdom of Judah was taken into exile to Babylon.

Jewish eschatology includes a belief that the Second Temple will be replaced by a future Third Temple.

According to the Bible, when the Jewish exiles returned to Jerusalem following a decree from Cyrus the Great (Ezra 1:1–4, 2 Chron 36:22–23), construction started at the original site of Solomon's Temple. After a relatively brief halt due to opposition from peoples who had filled the vacuum during the Jewish captivity (Ezra 4), work resumed ca. 521 BCE under Darius the Great (Ezra 5) and was completed during the sixth year of his reign (ca. 516 BCE), with the temple dedication taking place the following year.

The events take place in the second half of the 5th century BCE. Listed together with the Book of Ezra as Ezra-Nehemiah, it represents the final chapter in the historical narrative of the Hebrew Bible.[1]

The original core of the book, the first-person memoir, may have been combined with the core of the Book of Ezra around 400 BCE. Further editing probably continued into the Hellenistic era.[3]

The book tells how Nehemiah, at the court of the king in Susa, is informed that Jerusalem is without walls and resolves to restore them. The king appoints him as governor of the province Yehud Medinata and he travels to Jerusalem. There he rebuilds the walls, despite the opposition of Israel's enemies, and reforms the community in conformity with the law of Moses. After 12 years in Jerusalem, he returns to Susa but subsequently revisits Jerusalem. He finds that the Israelites have been backsliding and taking non-Jewish wives, and he stays in Jerusalem to enforce the Law.

Based on the biblical account, after the return from Babylonian captivity, arrangements were immediately made to reorganize the desolated Yehud Province after the demise of the Kingdom of Judah seventy years earlier. The body of pilgrims, forming a band of 42,360,[4] having completed the long and dreary journey of some four months, from the banks of the Euphrates to Jerusalem, were animated in all their proceedings by a strong religious impulse, and therefore one of their first concerns was to restore their ancient house of worship by rebuilding their destroyed Temple[5] and reinstituting the sacrificial rituals known as the korbanot.

On the invitation of Zerubbabel, the governor, who showed them a remarkable example of liberality by contributing personally 1,000 golden darics, besides other gifts, the people poured their gifts into the sacred treasury with great enthusiasm.[6] First they erected and dedicated the altar of God on the exact spot where it had formerly stood, and they then cleared away the charred heaps of debris which occupied the site of the old temple; and in the second month of the second year (535 BCE), amid great public excitement and rejoicing, the foundations of the Second Temple were laid. A wide interest was felt in this great movement, although it was regarded with mixed feelings by the spectators (Haggai 2:3, Zechariah 4:10</ref>).[5]

The Samaritans made proposals for co-operation in the work. Zerubbabel and the elders, however, declined all such cooperation, feeling that the Jews must build the Temple without help. Immediately evil reports were spread regarding the Jews. According to Ezra 4:5, the Samaritans sought to "frustrate their purpose" and sent messengers to Ecbatana and Susa, with the result that the work was suspended.[5]

Seven years later, Cyrus the Great, who allowed the Jews to return to their homeland and rebuild the Temple, died (2 Chronicles 36:22–23) and was succeeded by his son Cambyses. On his death, the "false Smerdis," an impostor, occupied the throne for some seven or eight months, and then Darius became king (522 BCE). In the second year of his rule the work of rebuilding the temple was resumed and carried forward to its completion (Ezra 5:6–6:15), under the stimulus of the earnest counsels and admonitions of the prophets Haggai and Zechariah. It was ready for consecration in the spring of 516 BCE, more than twenty years after the return from captivity. The Temple was completed on the third day of the month Adar, in the sixth year of the reign of Darius, amid great rejoicings on the part of all the people (Ezra 6:15,16), although it was evident that the Jews were no longer an independent people, but were subject to a foreign power. The Book of Haggai includes a prediction that the glory of the second temple would be greater than that of the first (Haggai 2:9).[5]

Some of the original artifacts from the Temple of Solomon are not mentioned in the sources after its destruction in 597 BCE, and are presumed lost. The Second Temple lacked the following holy articles:

The Bezalel Style

From the very beginnings of the Bezalel enterprise, there was a conscious effort to create a new and unique "Hebrew" style of art. Bezalel students and artisans sought inspiration in the native flora and fauna, notably the palm tree and the camel. They referenced archeological treasures, replicating Judean coins in filigree pieces and utilizing ancient mosaic floor designs in the carpet workshop. Traditional Jewish symbols such as the six-pointed Star of David and the seven-branched menorah were especially popular, as were architectural icons of the Holy Land. Biblical heroes, "exotic" Jewish ethnic types, modern halutzim (pioneers), and Zionist luminaries were also common subjects. Perhaps the most innovative "Hebrew" artistic creation of the Bezalel School was the decorative use of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet. Influenced both by Art Nouveau European typography and Islamic calligraphy, Hebrew letters served as a distinct decorative motif found on nearly every object created at Bezalel.

Bible with Bezalel Binding

This elaborate silver binding is the work of the two most renowned artists of the Bezalel School, Ze'ev Raban and Meir Gur-Arie. In addition to teaching at Bezalel, the two founded the Industrial Art Studio in 1923, which continued to operate after the closing of the school in 1929.

Three ivory medallions are set into the binding. On the front cover is an ivory plaque of the Tablets of the Law, guarded by the cherubim, here depicted as winged lions. On the back cover, four winged creatures, representing Ezekiel's vision of the Chariot of God, encircle an ivory roundel that portrays Jews praying at the Western Wall, the last standing remnant of the Temple. On the spine, a vertical plaque bears the Hebrew word TaNaKH, the acronym for Torah, Nevi'im, and Ketuvim (Pentateuch, Prophets, and Writings), the three sections of the Hebrew Bible.

Solomon's Temple

According to the Hebrew Bible, Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple, was the Holy Temple (Hebrew: בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ: Beit HaMikdash) in ancient Jerusalem before its destruction by Nebuchadnezzar II after the Siege of Jerusalem of 587 BCE and its subsequent replacement with the Second Temple in the 6th century BCE.

The Hebrew Bible states that the temple was constructed under Solomon, king of the United Kingdom of Israel and Judah and that during the Kingdom of Judah, the temple was dedicated to Yahweh, and is said to have housed the Ark of the Covenant. Jewish historian Josephus says that "the temple was burnt four hundred and seventy years, six months, and ten days after it was built",[1] although rabbinic sources state that the First Temple stood for 410 years and, based on the 2nd-century work Seder Olam Rabbah, place construction in 832 BCE and destruction in 422 BCE, 165 years later than secular estimates.

Bezalel and Oholiab

What skills did Bezalel and Oholiab possess? What does this say about the way the Spirit of God equips people for leadership? Why might God have equipped them with people skills as well as artistic and practical skills? How would each be needed in building the Tabernacle?

REFLECT: When told everything to do and exactly how to do it, how do you typically respond? If given the spiritual and physical resources to do it, and protected from overworking, how do you respond?

Not only does ADONAI give the details and specifications for the building of the Tabernacle, but He also personally selected who would oversee the work. Bezalel was to have overall charge of the building with Oholiab as his assistant. Without a doubt these men were selected because of their superior talent and previous experience. God promised that Bezalel would be filled with the Spirit of God. The construction of the Tabernacle was no small task. It would take skill and imagination. For this responsibility the LORD chose the best and gave them divine help.

Then ADONAI said to Moses His prophet: See, I have chosen Bezalel son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah. It is unusual to mention the names of both a father and grandfather together. But the rabbis teach that Hur was murdered for opposing the making of the golden calf. If true, Hur’s life was redeemed in the work of his grandson, who fashioned gold into the dwelling of the living God.505 And I have filled him with the Spirit of God, with skill, ability and knowledge in all kinds of crafts, to make artistic designs for work in gold, silver and bronze, to cut and set stones, to work in wood, and to engage in all kinds of craftsmanship (31:1-5, 35:30-33, 38:22). Bezalel was filled, or controlled, by the Holy Spirit to do his ministry. The rabbis also teach that Bezalel was only thirteen when selected by God to do the work of constructing the Tabernacle.

In addition to Bezalel, ADONAI appointed Oholiab son of Ahisamach, of the tribe of Dan to help him. It is interesting to notice that Hiram, the chief artist Solomon employed to make the ornamental work of the Temple was also from the tribe of Dan (Second Chronicles 2:13-14). And God gave both of them the ability to teach others (35:34). Although all of the craftsmenpossessed skill, literally wise of heart, but only Bezalel was filled with the Spirit of God. The supervisors’ names were appropriate indeed, since Bezalel means, in the Shadow of God, and Oholiab means, God the Father is My Tent.

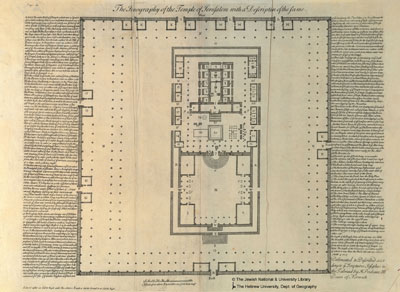

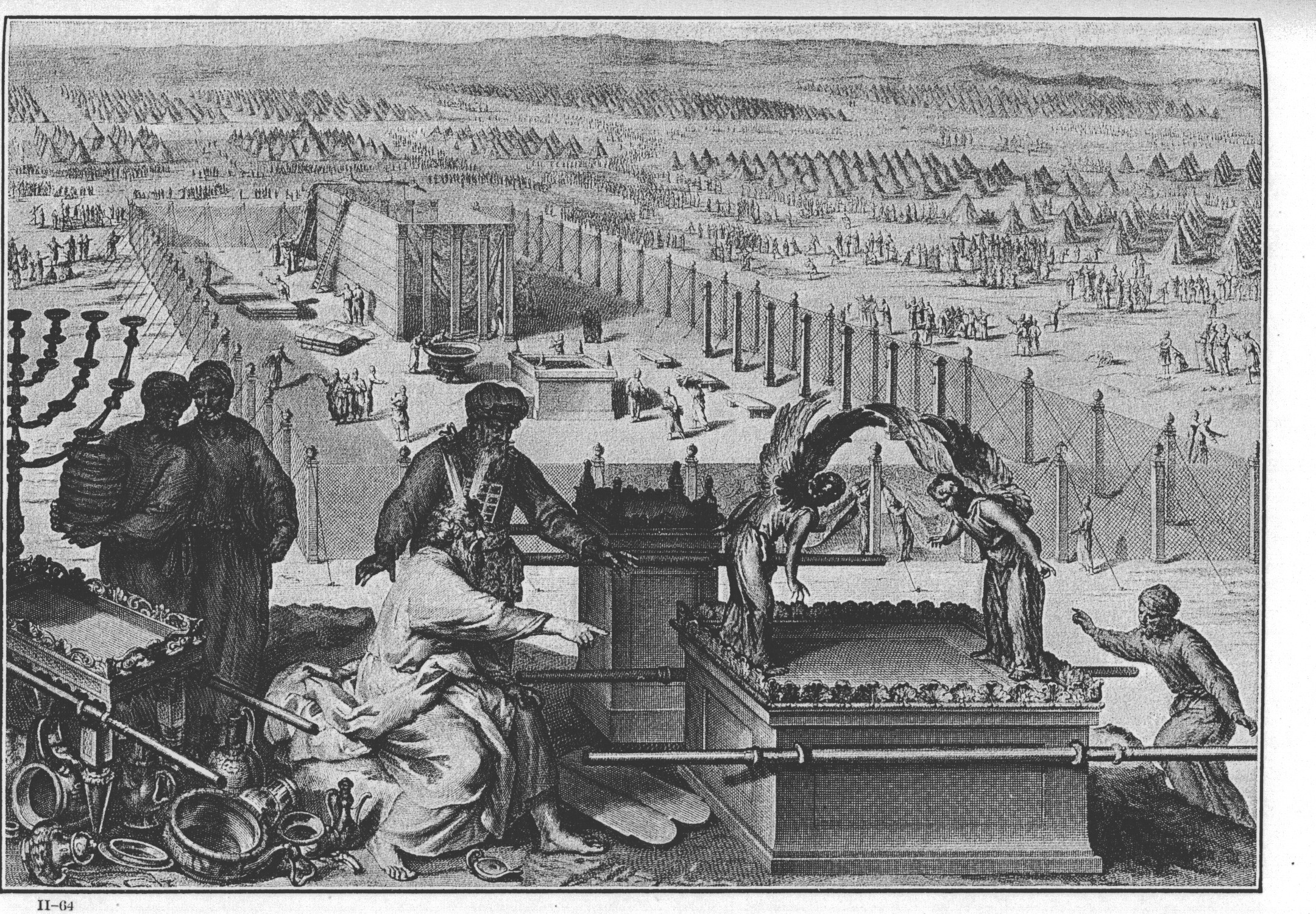

Tabernacle

The Tabernacle (Hebrew: מִשְׁכַּן, mishkan, "residence" or "dwelling place"), according to the Hebrew Bible, was the portable earthly meeting place of God with the children of Israel from the time of the Exodus from Egypt through the conquering of the land of Canaan. Built of woven layers of curtains along with 48 standing boards clad with polished gold and held in place by 5 bars per side with the middle bar shooting through from end to end and other items made from the gold, silver, brass, furs, jewels, and other valuable materials taken out of Egypt at God's orders, and according to specifications revealed by Yahweh (God) to Moses at Mount Sinai, it was transported [1] by the Israelites on their journey through the wilderness and their conquest of the Promised Land. Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem superseded it as the dwelling-place of God some 300 years later.

The main source for the account of the construction of the Tabernacle is the biblical Book of Exodus, specifically Exodus 25–31 and 35–40. It describes an inner shrine, the Holy of Holies, which housed the Ark of the Covenant, which in turn was under the veil of the covering suspended by four pillars and an outer chamber (the "Holy Place"), containing beaten gold made into what is generally described as a lamp-stand or candlestick featuring a central shaft incorporating four almond-shaped bowls and six branches, each holding three bowls shaped like almonds and blossoms, 22 in all. It was standing diagonally, partially covering a table for showbread and with its seven oil lamps over against it to give light along with the altar of incense.[2]

This description is generally identified as part of the Priestly source ("P"),[2] written in the sixth or fifth century BCE. However whilst the first Priestly source takes the form of instructions, the second is largely a repetition of the first in the past tense, i.e., it describes the execution of the instructions.[3] Many scholars contend that it is of a far later date than the time of Moses, and that the description reflects the structure of Solomon's Temple, while some hold that the description derives from memories of a real pre-monarchic shrine, perhaps the sanctuary at Shiloh.[2] Traditional scholars contend that it describes an actual tabernacle used in the time of Moses and thereafter.[4]According to historical criticism, an earlier, pre-exilic source, the Elohist ("E"), describes the Tabernacle as a simple tent-sanctuary.[2]

Bezalel

In Exodus 31:1-6 and chapters 36 to 39, Bezalel (Hebrew: בְּצַלְאֵל, also transcribed as Betzalel and most accurately as Bəṣalʼēl), was the chief artisan of the Tabernacle[1] and was in charge of building the Ark of the Covenant, assisted by Aholiab. The section in chapter 31 describes his selection as chief artisan, in the context of Moses' vision of how God wanted the tabernacle to be constructed, and chapters 36 to 39 recount the construction process undertaken by Bezalel, Aholiab and every gifted artisan and willing worker, in accordance with the vision.

Elsewhere in the Bible the name occurs only in the genealogical lists of the Book of Chronicles, but according to cuneiform inscriptions a variant form of the same, "Ẓil-Bêl," was borne by a king of Gaza who was a contemporary of Hezekiah and Manasseh.

The name "Bezalel" means "in the shadow [protection] of God." Bezalel is described in the genealogical lists as the son of Uri (Exodus 31:1), the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah (I Chronicles 2:18, 19, 20, 50). He was said to be highly gifted as a workman, showing great skill and originality in engraving precious metals and stones and in wood-carving. He was also a master-workman, having many apprentices under him whom he instructed in the arts (Exodus 35:30-35). According to the narrative in Exodus, he was called and endowed by God to direct the construction of the tent of meeting and its sacred furniture, and also to prepare the priests' garments and the oil and incense required for the service.

He was also in charge of the holy oils, incense and priestly vestments.[2] Caleb was his great-grandfather.

The rabbinical tradition relates that when God determined to appoint Bezalel architect of the desert Tabernacle, He asked Moses whether the choice were agreeable to him, and received the reply: "Lord, if he is acceptable to Thee, surely he must be so to me!" At God's command, however, the choice was referred to the people for approval and was endorsed by them. Moses thereupon commanded Bezalel to set about making the Tabernacle, the holy Ark, and the sacred utensils. It is to be noted, however, that Moses mentioned these in somewhat inverted order, putting the Tabernacle last (compare Exodus 25:10, 26:1 et seq., with Exodus 31:1-10). Bezalel sagely suggested to him that men usually build the house first and afterward provide the furnishings; but that, inasmuch as Moses had ordered the Tabernacle to be built last, there was probably some mistake and God's command must have run differently. Compare also Philo, "Leg. Alleg."

Bezalel possessed such great wisdom that he could combine those letters of the alphabet with which heaven and earth were created; this being the meaning of the statement (Exodus 31:3): "I have filled him . . . with wisdom and knowledge," which were the implements by means of which God created the world, as stated in Proverbs 3:19, 20 (Berakhot 55a). By virtue of his profound wisdom, Bezalel succeeded in erecting a sanctuary which seemed a fit abiding-place for God, who is so exalted in time and space (Exodus R. 34:1; Numbers R. 12:3; Midrash Teh. 91). The candlestick of the sanctuary was of so complicated a nature that Moses could not comprehend it, although God twice showed him a heavenly model; but when he described it to Bezalel, the latter understood immediately, and made it at once; whereupon Moses expressed his admiration for the quick wisdom of Bezalel, saying again that he must have been "in the shadow of God" (Hebrew, "beẓel El") when the heavenly models were shown him (Numbers R. 15:10; compare Exodus R. 1. 2; Berakhot l.c.). Bezalel is said to have been only thirteen years of age when he accomplished his great work (Sanhedrin 69b); he owed his wisdom to the merits of pious parents; his grandfather being Hur and his grandmother Miriam, he was thus a grandnephew of Moses (Exodus R. 48:3, 4).

Zionism

The first international gathering of Zionists took place in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897 and was dedicated to reestablishing a Jewish presence in the Land of Israel. There was, however, sharp dissension among the early adherents of the movement. "Political Zionists" were focused exclusively on the acquisition of an internationally recognized charter; "Cultural Zionists" championed a spiritual revival focused on Jewish culture in the Land of Israel; and "Practical Zionists" emphasized the more concrete methods of attaining Zionist goals: aliyah (immigration), rural settlement, and the founding of educational institutions in Palestine.

Despite these wide ideological gaps among the Zionist factions, the initial article of the "Basel Program," the manifesto adopted at the First Zionist Congress, called for the settlement in Palestine of Jewish artisans and tradesmen. Though Schatz was greatly inspired by the position of the Cultural Zionists, in the end it was Otto Warburg, Theodor Herzl's successor and a Practical Zionist, who stated in 1905 that "craftsmanship and home industry would thrive in Eretz Israel, if a national museum and a Jewish academy would be established." The support of the Zionist movement paved the way for the bold attempt to link economic self-reliance with the creation of a national Jewish artistic identity.

* Cultural Zionism (Hebrew: צִיּוֹנוּת רוּחָנִית, translit. Tsiyonut ruchanit) is a strain of the concept of Zionism that values creating a Jewish state with its own secular Jewish culture and history, including language and historical roots, rather than other Zionist ideas such as political Zionism.

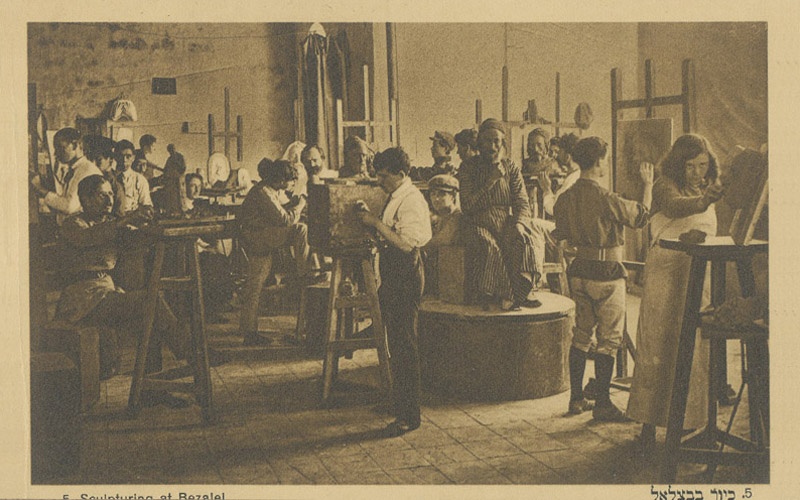

Bezalel Workshop, School & Museum

WORKSHOPS

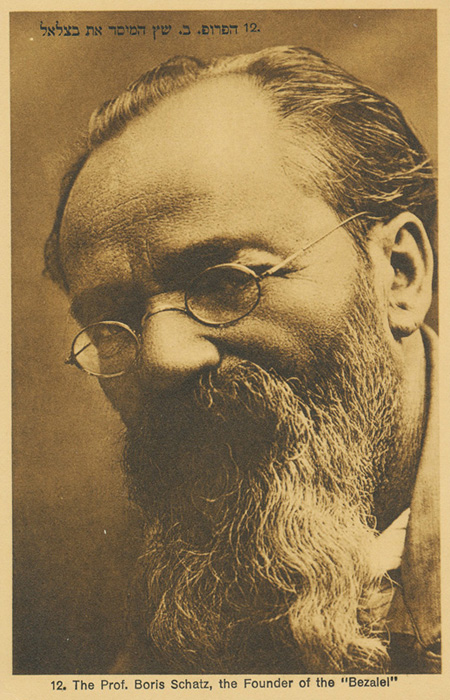

Boris Schatz and Students, Sculpture Class ca. 1914

Schatz's supporters in Berlin formed a committee called the "Bezalel Society for Establishing Jewish Cottage Industries and Crafts in Palestine" whose primary goal was to oversee the creation of a network of artisan workshops. These were meant to provide employment for the impoverished Jews of Ottoman-ruled Jerusalem by producing goods for local tourists as well as for export to the Jews of the Diaspora. The first workshop to open its doors was the carpetweaving department in 1906, followed by workshops for metalwork, ceramics, woodcarving, basketry, lithography, and photography.

SCHOOL

With few students and fewer qualified teachers, the school in its early years was particularly prone to setbacks in its development. Schatz's position as the only teacher of drawing, painting, and sculpture for nearly three years ensured that his artistic preferences and taste served as the primary influence for Bezalel students. The close connection between the school and the workshops was quite evident and the emphasis on decorative arts was clearly manifested in the curriculum. A student's typical day included at least two hours of practice in one of the workshop disciplines. Hebrew was taught six hours a week, alongside classes in art history, perspective, and anatomy.

MUSEUM

Postcard

Shmuel Ben-David (1884–1927)

Published in a postcard album by Yaakov Ben-Dov, 1926

Private Collection

Schatz began collecting materials for a museum as soon as he arrived in Palestine. Opened to the public in 1912, the museum featured native flora and fauna that Schatz hoped would serve as inspiration for the students and artisans. It also included an ethnographic and archaeological division comprising locally discovered artifacts and traditional Jewish ritual objects. Finally, there was a small fine arts section for which Schatz assiduously sought out works created by Jewish artists or depicting Jewish themes. Mordechai Narkiss, a student of Schatz's, served as head of the museum from the mid 1920s until his death in 1957. Under his leadership the collection expanded to international dimensions and incorporated objects as diverse as African art and Renaissance drawings. In 1965, the collections of the Bezalel Museum became the core of the newly founded Israel Museum.

Boris Schatz

Boris (Zalman Dov Baruch) Schatz was born to a traditional Jewish family in a small village near Kovno, Lithuania, and as a young man pursued religious studies in Vilna. It was there that Schatz first engaged with the two ideals that would permanently impact his life: art and Zionism. Dividing his days between yeshiva and art school, Schatz also joined a local Zionist group. He continued his art studies in Warsaw and Paris, enjoying a moderate level of artistic success as a sculptor.

In 1895, at the invitation of the King of Bulgaria, Schatz relocated to Sofia, where he taught at the Art Academy and became enmeshed in the project to create a national Bulgarian artistic identity. Schatz left Bulgaria in 1903 after his wife abandoned him for one of his students. That same year, the Kishinev pogrom roiled the entire Jewish world and pushed many into a strong embrace of Zionist ideology. In Schatz, it rekindled a Jewish consciousness that was reflected in his artistic production, now greatly expanded by the use of Jewish themes and characters.

During the years he spent in Bulgaria, Boris Schatz was particularly impressed by the development of home industries for the production of art. He reasoned that if Bulgaria, a small agricultural nation, could maintain a school with numerous departments for the development and commercial distribution of arts and crafts, a similar model could work for Jewish pioneers in Palestine. The dream of creating a new Jewish artistic ethos in the Land of Israel led Schatz to travel to Vienna in 1904 and seek out the blessing of the founder and leader of the Zionist movement, Theodor Herzl. Following Herzl's death later that year, Schatz re-presented his idea to several leading Zionists in Berlin who assumed responsibility for the project and its funding.

Schatz arrived in Palestine in early 1906, accompanied by only two teachers and two students. He immediately embarked on the daunting tasks of recruiting students, finding an appropriate building, and creating workshops. In the coming years, the school would grow to encompass numerous instructional departments, dozens of craft workshops, and a museum, all under the rubric "Bezalel."

The Last Supper - Leonardo da Vinci

The Last Supper - Leonardo da Vinci

by Ghenadie Sontu

oil on canvas, 120 x 60 cm, 2016

Private Collection

The Last Supper measures 460 cm × 880 cm (180 in × 350 in) and covers an end wall of the dining hall at the monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy. The theme was a traditional one for refectories, although the room was not a refectory at the time that Leonardo painted it. The main church building had only recently been completed (in 1498), but was remodeled by Bramante, hired by Ludovico Sforza to build a Sforza family mausoleum.[2] The painting was commissioned by Sforza to be the centerpiece of the mausoleum.[3] The lunettes above the main painting, formed by the triple arched ceiling of the refectory, are painted with Sforza coats-of-arms. The opposite wall of the refectory is covered by the Crucifixion fresco by Giovanni Donato da Montorfano, to which Leonardo added figures of the Sforza family in tempera. (These figures have deteriorated in much the same way as has The Last Supper.) Leonardo began work on The Last Supper in 1495 and completed it in 1498—he did not work on the painting continuously. The beginning date is not certain, as the archives of the convent for the period have been destroyed, and a document dated 1497 indicates that the painting was nearly completed at that date.[4]One story goes that a prior from the monastery complained to Leonardo about the delay, enraging him. He wrote to the head of the monastery, explaining he had been struggling to find the perfect villainous face for Judas, and that if he could not find a face corresponding with what he had in mind, he would use the features of the prior who complained.[5][6]

A study for The Last Supper from Leonardo's notebooks showing nine apostles identified by names written above their heads

Fragment of the "The Last Supper of Leonardo da Vinci" by Ghenadie Sontu

oil on canvas, 120 x 60 cm, 2016

Private Collection

The Last Supper specifically portrays the reaction given by each apostle when Jesus said one of them would betray him. All twelve apostles have different reactions to the news, with various degrees of anger and shock. The apostles are identified from a manuscript[7] (The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci p. 232) with their names found in the 19th century. (Before this, only Judas, Peter, John and Jesus were positively identified.) From left to right, according to the apostles' heads: Bartholomew, James, son of Alphaeus, and Andrew form a group of three; all are surprised. Judas Iscariot, Peter, and John form another group of three. Judas is wearing green and blue and is in shadow, looking rather withdrawn and taken aback by the sudden revelation of his plan. He is clutching a small bag, perhaps signifying the silver given to him as payment to betray Jesus, or perhaps a reference to his role within the 12 disciples as treasurer.[8] He is also tipping over the salt cellar. This may be related to the near-Eastern expression to "betray the salt" meaning to betray one's Master. He is the only person to have his elbow on the table and his head is also horizontally the lowest of anyone in the painting. Peter looks angry and is holding a knife pointed away from Christ, perhaps foreshadowing his violent reaction in Gethsemane during Jesus' arrest. The youngest apostle, John, appears to swoon. Jesus

- Apostle Thomas, James the Greater, and Philip are the next group of three. Thomas is clearly upset; the raised index finger foreshadows his incredulity of the Resurrection. James the Greater looks stunned, with his arms in the air. Meanwhile, Philip appears to be requesting some explanation.

- Matthew, Jude Thaddeus, and Simon the Zealot are the final group of three. Both Jude Thaddeus and Matthew are turned toward Simon, perhaps to find out if he has any answer to their initial questions.

In common with other depictions of the Last Supper from this period, Leonardo seats the diners on one side of the table, so that none of them has his back to the viewer. Most previous depictions excluded Judas by placing him alone on the opposite side of the table from the other eleven disciples and Jesus, or placing halos around all the disciples except Judas. Leonardo instead has Judas lean back into shadow. Jesus is predicting that his betrayer will take the bread at the same time he does to Saints Thomas and James to his left, who react in horror as Jesus points with his left hand to a piece of bread before them. Distracted by the conversation between John and Peter, Judas reaches for a different piece of bread not noticing Jesus too stretching out with his right hand towards it (Matthew 26: 23). The angles and lighting draw attention to Jesus, whose head is located at the vanishing point for all perspective lines.

The painting contains several references to the number 3, which represents the Christian belief in the Holy Trinity. The Apostles are seated in groupings of three; there are three windows behind Jesus; and the shape of Jesus' figure resembles a triangle. There may have been other references that have since been lost as the painting deteriorated.